Figure 1: Outsourcing market growth — business drivers.                                        CROs = contract research organizations      CMOs = contract manufacturing organizations  CDMOs = contract development and manufacturing organizations

The analytical field for biologics has evolved greatly over the past 30 years, and the underlying growth has shifted from biopharmaceutical companies to contract research organizations (CROs). The global biopharmaceutical market is growing annually at >15%, making it the largest and consistently fastest growing segment of the healthcare industry with annual sales in excess of US$200 billion. Contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) are expanding capacity by building new cost-efficient facilities, reflecting market demand. Many product sponsors are outsourcing, some even increasing their outsourced work.

Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry is consolidating through acquisitions and mergers as well as forming strategic alliances. That represents a minor threat to some CMOs by shrinking their client market. Currently the CMO market is very fragmented, with hundreds of companies across the globe — and it also is undergoing some consolidation, which is key to improving profitability. Late in 2015, the total global value for the CMO market was expected to increase from $72 billion to about $110 billion by 2020 (1), with an annual growth rate of >8%. Biosimilars will contribute significantly to that growth, reaching $30 billion by 2020 (a >60% compounded annual growth).

Factors Driving Market Growth

The biologics contract manufacturing market is relatively underdeveloped compared with the similar market that covers small molecules. But it should grow rapidly to $60 billion by 2020 as companies address complex biomanufacturing processes and obtain the necessary skill sets to get such work done — again very different from those for the small-molecule market (1). Within biologics, furthermore, mammalian cell culture also is relatively underdeveloped among CMOs, but it represents a significant opportunity to grow to $10 billion by 2020.

Of the four main market contributors — biosimilars, biomanufacturing, mammalian cell culture, and bio/analytical method development — the latter is the smallest segment. Although its activities currently lag behind the other three, they do represent great potential for future growth (to $10 billion by 2020) as CROs emerge and build more entrenched relationships with biopharmaceutical companies.

As Figure 1 shows, the global contract manufacturing market for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and intermediates forms the foundation of business drivers for this market’s growth. It’s expected to increase from $56 billion in 2015 to over $80 billion in 2020, an annual growth rate of >8% (1). On top of that, outsourcing of finished-dose formulations is expected to increase from $16 billion in 2015 to $25 billion by 2020, an annual growth rate of >9%. With all of that demand and the capital-intensive nature of the business that comes along with it (the facility/equipment requirements and associated skill sets), many pharmaceutical companies see the advantages of contracting or partnering with service providers. Even large sponsors would rather focus on core areas of their own competencies, allocating resources, expertise, and technologies toward new proprietary medicines.

CROs and contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) are striving to provide a greater value proposition by engaging clients during the early lifecycle stage of their projects and thus establishing long-term relationships. So CROs, CMOs, and CDMOs are consolidating their businesses to improve profitability in this crowded market. Thus, large organizations can expand for geographic presence and penetrate niche markets, whereas small companies leverage the technical expertise (and resources) of larger ones.

Some medical and technical drivers for market growth include a global focus on new and complex disease areas, with much growth in emerging markets. The patent cliff has threatened many blockbuster biotherapeutics for a number of years and will continue do so. Meanwhile, refinement of the contract market is bringing contract research and manufacturing together into CDMOs. They provide sponsors with a one-stop shop that can be integrated early in the biopharmaceutical value chain.

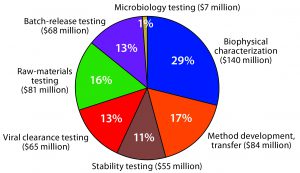

Figure 2: US analytical services market for biologics — $500 million (Source: PharmaSource development expenditures model and BPTC/BioPlan Associates)

CDMOs serve five primary market segments: applied research (discovery and pharmacokinetics); nonclinical research (analytical, bioanalytical, toxicity, preclinical); clinical research; chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (drug substance, drug product, microbiological testing); and other. The “other” segment includes a broad range of services from consultancies and small companies (e.g., offering business development and information technology services) and from larger companies (e.g., covering supply chain management, distribution, and staffing). Figure 2 depicts the biologics analytical services market in the United States based on data from a couple years ago. We have since then far surpassed the $500 million market size.

Some small-molecule companies are moving into biologics with limited expertise. Regulatory requirements are evolving, and the importance of moving candidates into clinical testing as fast as possible is increasing. Shorter timelines are moving some testing up earlier in development, which is increasing market size, but only for those companies that truly do have the technical capability. New capital-intensive, specialized technologies are making earlier and broader testing much more efficient than it was even a few years ago. Bioassays are the number-one most outsourced service by biomanufacturers currently in the United States — and also first in expected growth.

Outsourcing Options

Until recently, most outsourcing business drivers have been reactive, functional, or financial in nature. For example, a merger might drive installation of a new sourcing model (reactive). A small company may not have good laboratory or manufacturing practice (GLP, GMP) capabilities for supporting clinical trials, drug stability, or manufacturing (functional). A midsized company might see outsourcing as the only way to compete with larger organizations (financial). Those approaches are appropriate for short-term needs, but they are inefficient and ineffective for long-term success and profitability.

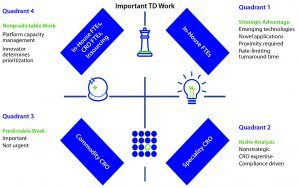

A Strategy Model: When two or more parties begin with a candid, transparent, and well thought-out process, a strategic partnership may develop that fully integrates internal and external human capital resources. In late 2015, Biogen published a four-quadrant strategic sourcing model in Scientific Computing, which the company has implemented within its technical development analytical team, although the model can be applied to any part of the business (2). Figure 3 is based on that model.

Strategic work often falles into two categories: proprietary work that directly facilitates material generation or process development/optimization within a company (e.g., the manufacturing process itself or data analysis related to generation of product) and proximal work (which benefits from proximity to the business). For analytical functions, the latter work is strategically dominant because speed is important.

Routine work often is defined as “habitual or mechanical performance of an established procedure.” As an industry, we should avoid using this term. Outsourcing decisions traditionally have been made to outsource “routine” work, and such work often is considered to be less important or less valuable than other work. By extension, a corporate organization can be less willing to invest in such work. No work should be thought of as less important or less valuable.

Based on the published model (Figure 3), a client’s efforts should be focused only on important work, whether that is urgent (right) or not (left). The former goes hand-in-hand with strategic importance (e.g., something coming off a production line or a data set someone is waiting for to make a decision). Important and urgent work should be performed internally because it might require an emerging technology or novel applications of existing technologies. Proximity also may be a requirement, or turnaround time also can be limiting.

What happens when internal resources become limited? Doing some of that work with a CRO might be the next-best option. Using a full-time equivalent (FTE) team limits the number of people working on a given project and allows for the team’s priorities to be adjusted quickly. For example, it might need to stay aligned with a manufacturing function or the timing of certain process development functions. A great deal of capacity management and prioritization would be involved here. The model describes this work as “nonpredictable.” Combined reprioritization and capacity management makes it both nonpredictable and important.

Also, on the important and nonurgent side of the model is predictable work (Figure 3, lower left). Think of predictable work as that governed by a qualified or validated method and protocol. A method’s maturity provides assurance that the work will produce meaningful results. The protocol regulates how much and when work is executed and when it is due. This predictable work is important but not urgent — and certainly not routine.

The fourth quadrant (Figure 3, lower right) contains work that is important, but not strategic. This work generally would be governed by regulatory agencies: e.g., extractables and leachables testing, trace-metals analysis, and even bioassays. Here, a CRO can offer specific skill sets and advanced instrumentation to address the needs of multiple sponsors with a permanent team.

Putting the Model to Practice: At Catalent Biologics, we first agreed on standard terminology embedded within the model, then set teams of subject matter experts (SMEs) to identify strategic, predictable, nonpredictable, and niche work activities across two work streams: antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and gene therapies. Quickly we learned that nothing falls into any particular quadrant every time, so we applied the 80/20 rule fairly liberally. Our conversations led to the start of a potential ASO work-stream collaboration. The model prioritizes work performed internally and externally, which together with flexibility drove our discussion about ASOs. Site proximity allowed us to move important and urgent work into a program that might be benefited by a type of FTE resourcing model. It just so happened that the laboratory team that would perform such work is located only a couple of miles from Biogen’s manufacturing plant.

As our conversations advanced over the following months, circumstances changed, and we started talking about an additional work stream (proteins and peptides). We started to think that nonstrategic work might be ideal for Biogen to outsource because it was a mature work stream within the organization. Finally, we thought that gene therapy work — the sponsor’s newest endeavor — should be performed and driven mostly by Biogen’s internal teams. That is not to say that the company won’t outsource any such work, but the maturity of the work flow is best supported by internal resources. After some months of discussion, both parties believe that this is probably the best option for the partnership.

About eight months into that process, we identified many opportunities to increase the probability of a successful partnership. For example, instrumentation alignment and collaboration with equipment vendors moved things rapidly through their respective work streams. Automation became an early focal point of discussion. We already shared common platforms, so we can plan for manual method transfer, manual-to-automated development projects, and automated-to-automated transfer. Now we are discussing data-transfer platforms and planned collaborations with data analysis vendors around common challenges. Turn-around times definitely will be shortened for everything from business agreements to wet-laboratory work.

CROs, CMOs, and CDMOs will face situations in which sponsors will maintain proprietary work internally. And when they run out of internal bandwidth, an FTE type of program can offer them flexibility to respond to changing priorities. When it comes to nonurgent, protocol-driven work that a fee-for-service team can perform, we can offer that platform as an outsourcing strategy too. CROs have a current advantage in that they can hire smart, capable people and bring in the most advanced equipment to form and sustain specialized teams for niche work, and those capabilities can be spread across multiple innovator partnerships.

Building Relationships

Our businesses are growing and consolidating. Outsourcing will continue, and evolution will continue. It is becoming more about strategic partnerships and less about transactional agreements. And nothing about this work is easy or routine. CDMOs can and do hire the same types of talented scientists and can and do implement the same advanced instrumentation that sponsor companies do. The gap in the work product is not defined by the CDMO’s people or instrumentation, but rather by the nature of how they are allowed to partner with their clients. We hope to change what is possible. Relationships take time. They don’t always progress as intended, but they do develop, and things work out in the end.

Acknowledgments

At Biogen: Svetlana Bergelson, Tobias Blackburn, Len Blackwell, Brian Fahie, Dan Gage, Evan Guggenheim, Shiva Krupa, Ruiting Liang, Kip Lowrey, Catherine Ramsey, and Jessica Stolee. At Catalent Biologics: Andrew Argo, Tami Conley, Brandon Cuthbertson, Chris Hepler, Russ Miller, Doug Morgensen, Joe Nawrocki, Anne Marie Rogan, Andrew Sandford, and Brian Woodrow.

References

1 Global Pharmaceutical CMO Market: Emerging Business Models Drive Transformation. Frost & Sullivan: San Antonio, TX, 2016.

2 Fahie B, Guggenheim E. The Business Challenges of Externalizing R&D. Scientific Computing 14 December 2015; www.scientificcomputing.com/article/2015/12/business-challenges-externalizing-rd.

Corresponding author Michael Merges is director of strategic growth for biologics analytical services at Catalent Biologics, 160 Pharma Drive, Morrisville, NC 27560; 1-919-809-4309; michael.merges@catalent.com; www.catalent.com. Brian Fahie is director of analytical development at Biogen in Cambridge, MA.