Biologics, primarily therapeutic antibodies and recombinant proteins, represent a growing share of the current drug market, with projected worldwide sales of about US$278 billion by 2020, partly because of their relatively high costs. Indeed, AbbVieâs therapeutic antibody Humira (adalimumab) is currently the top-selling drug in the world by sales but not even in the top 50 by the number of monthly prescriptions. Although the process for marketing generic versions of small molecules under the HatchâWaxman Act is well understood, the process for marketing biosimilars under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) still is being established and presents many unresolved questions.

Marketing biosimilars involves a very complex patent litigation procedure that potentially discourages biosimilar development, particularly while the courts are still determining issues left unresolved by Congress and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). As an alternative (or supplement) to patent litigation, biosimilar developers are beginning to make use of post-grant proceedings such as inter partes review (IPR) at the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to challenge blocking patents.

Herein we discuss strategic considerations for the use of post-grant proceedings in bringing greater certainty to biosimilar development, including analysis of those proceedings that have been filed to date.

Resolving Patent Disputes Under the BPCIAÂ

Until 2010, there was no mechanism in the United States for marketing biosimilars. Growing recognition of a need to provide incentives for developing new biologics while also permitting competition from generics led to implementation of the BPCIA in March 2010. The first biosimilar, Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz) marketed by Sandoz, achieved approval under this pathway in 2015 (1).

Similarly to the HatchâWaxman Act, the BPCIA provides an abbreviated pathway for obtaining FDA approval by allowing a biosimilar applicant to rely on clinical data associated with an approved reference product. A biosimilar must be ââhighly similar to the reference product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive componentsââ with ââno clinically meaningful differences between the biological product and the reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the productââ (2).

Notably, a biosimilar applicant can gain FDA approval for less than all of the indications, routes of administration, or delivery devices for which the reference product obtained approval (2). This allows a ââcarve-outââ scenario in which a biosimilar applicant can avoid specific patent protection surrounding a reference product. The BPCIA provides an innovator reference product with 12 years of regulatory exclusivity, including four years in which the FDA will accept no biosimilar applications and eight years in which the FDA will accept such applications but grant no approval (2).

Also similarly to the HatchâWaxman Act, the BPCIA provides a mechanism for resolving patent disputes between biosimilar applicants and the reference-product sponsors (RPSs). However, significant differences exist between the two pathways (3): Under the HatchâWaxman Act, the holder of a new drug application (NDA) provides a list of all patents that reasonably would be infringed by a generic, as published in the Orange Book (4). A generic manufacturer can challenge those patents before marketing by filing a paragraph IV certification accompanying an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA), asserting that the patents are invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. The NDA holder can then sue the generic manufacturer and obtain a 30-month stay, during which the FDA will not approve the genericâs ANDA application (4).

The BPCIA pathway does not involve an Orange Book listing, a paragraph IV certification, or a 30-month stay. Instead, it contemplates a complex back-and-forth between the parties to establish patents to be litigated (referred to as a patent dance), followed by two waves of patent litigation. The process starts when the FDA accepts the biosimilar application, which provides a 20-day window for the applicant to provide a copy of its application, including manufacturing information, to the RPS (5).

Over a six-month period, the two parties exchange patent lists, including opinions on validity, enforceability, and infringement, negotiating which patents will be included in the first wave of litigation (5). A biosimilar applicant also is required to provide notice to the RPS within 180 days of commercial marketing. That provokes the second wave of patent litigation and allows the RPS to seek a preliminary injunction based on patents that were not litigated in the first wave (5).

Challenges to the BPCIAÂ

Early litigation challenges to the BPCIA are shaping our understanding of complex statutory requirements. Not surprisingly, biosimilar applicants would like to prevent the patent dance, at least in part because of its stringent and time-sensitive requirements for information disclosure, including about the biosimilar itself and about the biosimilar applicantâs invalidity and/or infringement contentions. As a result, litigation challenges to the BPCIA so far have focused on whether the patent dance is really a requirement.

Several cases have addressed the question of whether a biosimilar applicant can instigate a declaratory judgment action before filing a biosimilar application, which would bypass the need for the patent dance (6â9). However, this approach does not appear to be viable for circumventing the patent dance because in each case, the courts have found a lack of case or controversy, leading to dismissal.

In 2015, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit addressed the question of what would happen if a biosimilar applicant refused to partake in the patent dance following submission of a biosimilar application (10). Sandoz applied to the FDA in May 2014 for approval of a biosimilar of filgrastim (which is marketed by Amgen as Neupogen) (10). Although Sandoz informed Amgen that its application had been accepted by the FDA, it did not provide Amgen with a copy of its application or manufacturing information under 42 USC §262(l)(2)(A). Instead, Sandoz informed Amgen that it was entitled to sue under 42 USC §262(l)(9)(C) (10). The Federal Circuit found that Sandoz had acted within its rights under the BPCIA, holding that a biosimilar applicant is not required to disclose its biosimilar application to the RPS, and that the failure to do so represents an act of infringement, allowing the RPS to bring a declaratory judgment action under 42 USC §262(l)(9)(C) and 35 USC §271(e)(2)(C)(ii) (10). Thus, the BPCIA appears to provide a mechanism for biosimilar applicants to prevent the patent dance by allowing an RPS to bring a declaratory judgment action. It remains to be seen whether any biosimilar applicants will choose to partake in the patent dance if it is truly an optional process.

Other significant questions not yet resolved relate to whether it is mandatory under the BPCIA for a biosimilar applicant to provide 180-day notice before commercial marketing and, if so, whether an applicant can provide this notice before receiving FDA approval of a biosimilar. In Amgen v. Sandoz, the Federal Circuit held that â at least for a scenario in which a biosimilar applicant chooses not to partake in the patent dance â the 180-day notice is required and can be given only after FDA approval of a biosimilar (10). Sandoz has petitioned the Supreme Court to consider whether a biosimilar applicant can provide the requisite notice before obtaining FDA approval (11). Amgen has filed a conditional cross-petition requesting that, if the Supreme Court does review the case, then it also would review the patent dance is optional or mandatory (12). The US Supreme Court has solicited input from the solicitor general on those petitions (13).

Building on Amgen v. Sandoz, the Federal Circuit recently affirmed in Amgen v. Apotex a district court ruling that a biosimilar applicant must provide 180-day premarketing notice to the reference product sponsor even when a biosimilar applicant has participated in the patent dance (14). The two cases were decided by different panels, but unlike Amgen v. Sandoz, the Amgen v. Apotex decision was unanimous. Apotex has petitioned the Supreme Court to consider whether the 180-day notice is required for biosimilar applicants that comply with the patent dance (15).

One implication of the Amgen v. Apotex case is that it could lead to a de facto six-month extension of the 12-year regulatory exclusivity period provided to the RPS under the BPCIA. This is because the court confirmed that a biosimilar applicant can provide notice of commercial marketing only after obtaining a biosimilar product license, which is currently granted only upon expiry of a 12-year exclusivity period (14). The court addressed this issue by suggesting that the FDA could begin issuing biosimilar licenses earlier to allow a biosimilar applicant time to provide notice before the end of the exclusivity period (14). Accordingly, it is now up to the FDA to indicate whether it is willing to issue such âtemporaryâ or âtentativeâ licenses that would allow biosimilar applicants to comply with the 180-day notice provision in advance (and under what authority) and prevent the 12-year exclusivity from becoming 12.5 years.

Advantages of Post-Grant Proceedings Relative to BPCIA

The America Invents Act (AIA) implemented in 2012 shifted the patent litigation landscape by creating mechanisms for resolving patent disputes at the US Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as an alternative or supplement to litigation. As of 30 September 2016, 5,143 IPR petitions had been filed (16). In addition to IPR, post-grant proceedings include post-grant review (PGR) and covered business method patent review (CBM). However, the majority filed to date that are relevant for the biopharmaceutical industry are IPRs, because PGRs can be used only to challenge post-AIA patents, and CBMs are applicable only to patents covering business methods.

Table 1: Comparison of BPCIA and post-grand proceedings (IPR = inter partes review, PGR = post-grant review)

For biosimilars, post-grant proceedings offer many advantages relative to litigation and should be considered as part of any biosimilar development program. (Table 1) From a procedural perspective, a notable difference is that although only a biosimilar applicant can challenge a patent under the BPCIA and only within the strict guidelines of the BPCIA, in post-grant proceedings any party (other than the patent owner) can initiate a challenge. And the challenge is not tied to a biosimilar approval process. Accordingly, filing a post-grant proceeding could allow a biosimilar developer to clear blocking patents (or at least determine the strength of patent protection covering the reference product) earlier in the biosimilar development pathway, before making a major investment in developing a biologic.

Post-grant proceedings generally are faster and less expensive than litigation, partly because post-grant proceedings have a set timeline and because the scope of discovery is extremely reduced relative to litigation. Moreover, because of strict timelines, courts frequently will stay any concurrent litigation until the post-grant proceeding is decided.

Post-grant proceedings also offer several significant substantive advantages relative to litigation for the party challenging a patent. For example, such proceedings include a lower standard of proof (ââpreponderance of the evidenceââ instead of ââclear and convincing evidenceââ), a broader standard for claim construction (ââbroadest reasonable interpretationââ instead of ordinary and customary meaning in light of the claims, specification, and prosecution history), and a different judge and jury (an administrative patent judge used to finding patents to be unpatentable while performing both functions, instead of a district court judge and jury who are not so experienced at splitting those functions). All such differences serve to shift the scale toward a challenger at the PTAB, making it an attractive forum for biosimilar developers. Although some experts expressed initial concerns that patent owners could amend their claims and potentially strengthen their patents, those fears have proved largely unfounded in IPR proceedings. Very few patent owners have been able to make such amendments, at least in part because a patent owner is required to demonstrate patentability of amended claims.

Initially, the biopharmaceutical industry represented a small percentage of post-grant proceedings. That is partly because such proceedings are often filed concurrently with ongoing litigation and so are most common in highly litigious areas of technology such as electronics. But biologics require a long time for commercialization. So a post-grant filing is more likely to be part of a long-term business strategy. In addition, the majority of post-grant proceedings filed so far have been IPRs, which are limited to prior art grounds, whereas challenges under 35 USC §§112 and 101 have tended to play an important role in litigation of biopharmaceutical patents. PGRs (which are just starting to become available) will help to level that aspect of the playing field because they can be based on any statutory ground other than best mode.

Recent statistics reveal that biopharmaceutical post-grant proceedings are increasing. In particular, generic and biosimilar manufacturers are recognizing advantages of this pathway. The high success rates achieved so far also are compelling. For IPR petitions that have reached a final disposition as of 30 September 2016, out of 1,901 IPR trials that have been instituted (including all areas of technology), 53% have resulted in some or all instituted claims being cancelled (corresponding to 85% of trials that reached the final written decision stage) (16). For biosimilar developers, because many of the composition-of-matter patents covering brand-name biologics are close to expiry, post-grant proceedings represent a particularly promising strategy for attacking follow-on patents, such as those covering formulations or specific dosing regimens.

Insight from Early IPRs Challenging Biologics Patents

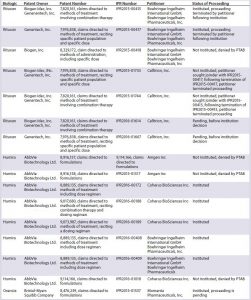

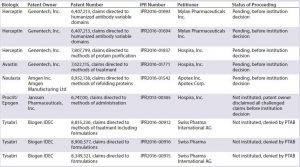

IPRs challenging patents covering brand-name biologics (recombinantly produced proteins such as antibodies) have been filed both by biosimilar developers directly and by other entities (Tables 2A and 2B). The first such IPRs to reach a final written decision were initiated by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. challenging patents covering Myozyme and Lumizyme, marketed by Genzyme (17â19). The challenged claims in those cases were broad method-of-treatment claims reciting mechanistic limitations and dosing limitations. The PTAB found all challenged claims to be unpatentable based on obviousness, stating that ââthe claimed subject matter was a product of routine clinical trial processesââ (19). The PTAB was unconvinced by the patent ownerâs arguments related to secondary considerations, finding an insufficient nexus between the evidence and the claim features (19). Although BioMarinâs motivation was to clear a path for a competing biologic rather than a biosimilar, the decisions have relevance for potential biosimilar developers because the result could allow earlier market entry for biosimilars.

Table 2B: Summary of inter partes review (IPR) challenges by biosimilar developers (PTAB = US Patent Trial and Appeal Board)

In a proceeding initiated by Phigenix Inc., challenging a patent covering Genentechâs Kadcyla, the PTAB reached the opposite outcome, upholding all of the challenged claims (20). Notably, the claims in this case were composition-of-matter claims. The PTAB agreed with the patent owner that someone of ordinary skill in the art would not have been motivated to combine the cited references, nor have had a reasonable expectation of success (20). Although the PTAB generally has not placed much emphasis on secondary considerations, in the analysis of picture claims covering Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine, Genentech), the PTAB found convincing evidence of longfelt need, unexpected results, and commercial success. And it found a sufficient nexus between the evidence and the claims (20). This finding may not be broadly applicable to challenges by biosimilar developers because establishing a nexus for composition-of-matter claims covering a product is understandably easier than establishing a nexus for claims in other patents, such as follow-on patents likely to be the subject of most challenges.

One example of a petition filed directly by a biosimilar developer challenging a patent covering a reference product is a petition filed by Hospira. The company was developing a biosimilar of epoetin alfa (EPO), marketed by Janssen as Procrit and by Amgen as Epogen. Hospira filed an IPR petition challenging claims covering methods of administration of EPO (21). The patent owner chose to disclaim all challenged claims, terminating the proceeding. This favorable result for Hospira provided the company with increased certainty at an early stage of its biosimilar development, before even submitting its application to the FDA (22).

Several biosimilar developers have filed IPR petitions challenging patents covering Rituxan (rituximab), a blockbuster therapeutic monoclonal antibody marketed in the United States by Genentech (Roche) and Biogen Idec. Out of three petitions filed by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals (BI), two were instituted, and a third was denied institution. (IPR2015-00415 and IPR2015-00417 were instituted while IPR2015-00418 was not instituted. Biogen Idec Inc. and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., are Wolf Greenfield clients, though the firm did not represent either company in these IPRs.) Following institution of the BI petitions, Celltrion filed IPR petitions challenging the same patents as BI and sought joinder with BIâs proceedings (23, 24). Those proceedings were terminated later when BI halted its Rituxan biosimilar development (25, 26). Celltrion has since refiled two petitions, which are currently pending before institution (27, 28).

Not surprising given the sales figures for Humira, multiple parties have filed IPR petitions challenging patents covering Humira. Two petitions filed by Amgen Inc. challenging formulation claims were denied institution (29, 30). Coherus BioSciences Inc. filed an additional petition challenging formulation claims, which also was denied institution (31). Five petitions filed by either BI or Coherus are challenging claims directed to methods of treatment including dosing regimens. They have been instituted and are currently pending (32â36).

Biosimilar developers also filed petitions challenging claims covering

- Orencia (abatacept, Bristol-Myers Squibb), with one petition instituted and currently pending (37)

- Herceptin (trastuzumab, Genentech), with three petitions pending, awaiting a decision on institution (38â40)

- Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech), with one petition pending, awaiting a decision on institution (41)

- Neulasta (pegfilgrastim, Amgen), with one petition pending, awaiting a decision on institution (45)

- Tysabri (natalizumab, Biogen), with three petitions denied institution (43â45).

Future Directions

Biosimilar developers are making increased use of post-grant proceedings. So far, it appears that broad mechanistic claims and follow-on patent claims (e.g., those covering methods of treating specific patient populations or specific dosing regimens) will be vulnerable to obviousness challenges at the PTAB, at least based on institution decisions and a small number of final written decisions. A rule change allowing patent owners to submit expert declaration evidence before the decision on institution has yet to reduce high rates of institution by strengthening the patent ownerâs position preinstitution. Considering the high overall success rate in IPRs and increased certainty that can be attained by clearing blocking patents early, post-grant proceedings likely will be incorporated into most, if not all, biosimilar development strategies.

References

1 Filgrastim-sndz. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 3 March 2015; www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm436953.htm.

2 Guidance for Industry: Biosimilars â Questions and Answers Regarding Implementation of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009. US Food and Drug Administation: Rockville, MD, April 2015.

3 Kowalchyk, Crowley-Weber. Biosimilars: Impact of Differences with Hatch-Waxman. Pharm. Pat. Analyst 2(1) 2013: 29â37.

4 USC Title 21, Chapter 9, Subchapter V, Part A, §§355: New Drugs. US Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, 2010.

5 USC Title 42, Chapter 6A, Subchapter II, Part F, Subpart 1, §§262: Regulation of Biological Products. US Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, 2015.

6 Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc. Northern District of California: 12 Nov. 2013.

7 Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd. v. Kennedy Trust for Rheumatology Research. Southern District of New York: 1 Dec. 2014.

8 Hospira Inc. v. Janssen Biotech Inc. Southern District of New York: 1 Dec. 2014.

9 Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc. No. 20141693, slip op. Federal Circuit: 5 Dec. 2014.

10 Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc. No. 20151499, slip op. Federal Circuit: 21 July 2015.

11 Sandoz Asks High Court to Review Biosimilar Case. Life Sciences Law and Industry Report. 19 February 2016.

12 Overly J. Amgen Hedges on Sandozâs High-Court Biosimilar Petition. Law 360, 22 March 2016; www.law360.com/articles/774698/amgen-hedges-on-sandozâs-high-court-biosimilar-petition.

13 Overly J. High Court Seeks US Take On SandozâAmgen Biosimilar Battle. Law 360, 20 June 2016; www.law360.com/articles/808627/high-court-seeks-us-take-on-sandoz-amgen-biosimilar-battle.

14 Amgen Inc. v. Apotex Inc. No. 2016-1308, 15. Federal Circuit 5 July 2016.

15 Overley J. Apotex Takes Biosimilar Case to Supreme Court. Law 360, 16 September 2016; www.law360.com/articles/840969/apotex-takes-biosimilar-case-to-supreme-court.

16 AIA Trial Statistics. United States Patent Office; www.uspto.gov/patents-application-process/appealing-patent-decisions/statistics/aia-trial-statistics.

17 Biomarin Pharmaceutical Inc. v. Genzyme Therapeutic Products Ltd. Partnership. Patent Trial and Appeal Board IPR2013-00534, 23 Feb. 2015.

18 Biomarin Pharmaceutical Inc. v. Duke University. Patent Trial and Appeal Board IPR2013-00535, 23 Feb. 2015.

19 Biomarin Pharmaceutical Inc. v. Genzyme Therapeutic Products Ltd. Partnership. Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR2013-00537, 23 Feb. 2015.

20 Phigenix Inc. v. Immunogen Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR2014-00676, 27 Oct. 2015.

21 Hospira, Inc. v. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR2013-00365, 24 Oct. 2013 (trial denied).

22 Liu Z, Royzman I. Biosimilar Makers Turn to IPRs Before Litigation under BPCIA. Biologics Blog 15 May 2015; www.biologicsblog.com/blog/biosimilar-makersturn-to-iprs-before-litigation-under-bpcia.

23 Celltrion Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2015-01733.

24 Celltrion Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. and Biogen Idec. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2015-01744.

25 Rin-Laures LH. PTAB Dismisses Biosimilar Companyâs IPR Petition without Prejudice When Petitioner Loses Its Expert. PTABWatch, 13 Oct. 2015.

26 Boehringer Ingelheim Stops Biosimilar Rituximab Development. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative 30 Oct. 2015; www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/BoehringerIngelheim-stops-biosimilar-rituximab-development.

27 Celltrion, Inc. v. Biogen, Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01614.

28 Celltrion, Inc. v. Genentech. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01667.

29 Amgen, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2015-01514.

30 Amgen, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2015-01517.

31 Coherus Biosciences, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01018; 9 Aug. 2016.

32 Coherus Biosciences, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00172, 17 May 2016.

33 Coherus Biosciences, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00188, 13 June 2016.

34 Coherus Biosciences, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00189, 13 June 2016.

35 Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00408, 7 July 2016.

36 Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00409, 7 July 2016.

37 Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. BristolMeyers Squibb Co. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2015-01537, 15 Jan. 2016.

38 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Genentech. Patent Trial and Appeal Board IPR2016-01693, 31 Aug. 2016.

39 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Genentech. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01694, 31 Aug. 2016.

40 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Hospira, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01837, 16 Sept. 2016.

41 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Hospira, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01771, 9 Sept. 2016.

42 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Apotex, Inc. v. Amgen, Inc. and Amgen Manufacturing Ltd. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-01542, 5 Aug. 2016.

43 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Swiss Pharma International AG v. Biogen Idec. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00912 (denied 17 Oct. 2016).

44 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Swiss Pharma International AG v. Biogen Idec. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00915 (denied 17 Oct. 2016).

45 Petition for Inter Partes Review: Swiss Pharma International AG v. Biogen Idec. Patent Trial and Appeal Board, IPR2016-00916 (denied 17 Oct. 2016).

Corresponding author Michael Siekman (msiekman@wolfgreenfield.com) is a shareholder and Oona Johnstone (ojohnstone@wolfgreenfield.com) is an associate in both the Biotechnology and Post-Grant Proceedings Groups at intellectual property law firm Wolf Greenfield in Boston.