Certain types of quality control (QC) testing are often outsourced by pharmaceutical companies, regardless of an organization’s size — typically because the company is either incapable of performing the assays in-house or does not wish to bring them into its facility. The decision to outsource may be based on

- the complexity of techniques involved

- special skills required for conducting the assays

- a need for biohazardous reagents such as radioisotopes

- limited testing frequency for the assays

- or (in biologics testing) because they require propagation and/or manipulation of potential biological contaminants, including positive controls, which present a risk to the purity and safety of biological products manufactured on site.

Examples of contracted testing include viral and mycoplasma safety studies with infectious positive control organisms, analytical testing using highly specialized equipment such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), and radiolabeling studies for metabolism or biodistribution. Fortunately, a number of contract research and testing organizations can and will perform such types of testing.

Much has been written about the rationales for and advantages of outsourcing manufacturing and/or testing services, selecting outsourcing partners, and optimizing sponsor/contractor relationships (1,2,3,4,5). In any such relationship, the contractee (contract giver) has responsibilities as well as the contractor (contract acceptor) — relating both to business and regulatory compliance. We will address the contractor’s responsibilities in a future article (6). The business realities and regulatory expectations associated with a pharmaceutical company’s use of a contract service organization must be considered in making a decision to outsource. The optimal and most defensible contract laboratory administration programs are those in which the practices described herein are formalized within internal quality systems, policies, and/or standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Contract Laboratory Selection

Selecting a contract test laboratory typically involves an assessment by the contractee of the laboratory’s technical capabilities, its available capacity, its regulatory track record (compliance history), testing facilities, quality systems, and assay pricing. Before or during the course of that assessment process, a confidentiality agreement may be necessary to protect the proprietary interests of both organizations. Thorough evaluation of a contractor’s quality systems will ensure that they meet a contractee’s requirements. Once all the quality and pricing considerations described below have been addressed, the contract laboratory can be approved.

Methods and Capacities: During evaluation of a laboratory’s technical capabilities and capacity, attention should be placed on the analytical methods themselves. Do the methods comply with relevant compendia or regulatory guidances? Are appropriate standards and/or controls used? Are assay invalid rates monitored — and if so, whatdo they look like? Are noncompendial methods validated? In evaluating capacity, the following also might be addressed:

- What is the normal lead time from sample submission to assay initiation?

- How long after assay completion are results reported?

- Can those times be minimized, and how much will that cost?

- Are appropriate instruments available, and are there redundancies in both the equipment used and trained operators for the assays?

- Are assay reagents, standards, and controls readily available and stocked at adequate levels? Are those inventories monitored to prevent unexpected delays in initiating and completing assays?

Compliance History: A contract laboratory supporting a sponsor’s QC needs is acting as an extension of that company’s QC group and is therefore subject to scrutiny by regulatory agencies during preapproval inspections. In addition, testing organizations are typically subject to routine inspection, depending on their geographical locations, by one or more regulatory agencies: e.g., the FDA in the United States, the EMEA in the European Union, the PMDA in Japan, and the COFEPRIS in Mexico. A sponsor may request an inspection history as well as redacted establishment inspection reports and responses from the contract laboratory either during on-site visits or through correspondence.

Depending on the nature of the laboratory’s business, it may be subject to inspection by other types of regulatory agencies. For example, if a lab performs animal testing, it could be inspected by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the USDA. Any testing laboratory can be inspected by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the United States. Although results of such inspections are not GMP related, the reports may be useful in due diligence because a contractor can be shut down or face sanction if it fails an audit by one of those organizations. And that can disrupt a contractee’s business.

Information obtained can be combined with a contractee’s own assessments of quality systems to form a clearer picture of the contract lab’s potential to successfully stand up to regulatory inspection. This helps uphold the contractee’s own high standards for QC testing.

Quality Systems: Evaluation of a contract testing organization’s quality systems is a required part of the selection process (7,8). Ordinarily this is done during on-site audits, when a potential contractee is allowed full access to a contractor’s quality manual, policy documents, and SOPs. Such documents are typically considered, along with procedural descriptions (e.g., protocols and method SOPs), to be proprietary and normally aren’t allowed to leave a testing facility. Particular attention should be paid to the laboratory’s procedures for data archiving, test sample login, change control, deviations/nonconformances, and investigation of unexpected and out-of-specification (OOS) results (7). The contractor’s policies for use of subcontractors should also be evaluated.

Numerous tools and checklists from both US and EU perspectives are available to help evaluate contract laboratory quality systems. For example, company-specific questionnaires may be developed and used to evaluate analytical chemistry (9,10) and biosafety or microbiology laboratories (11,12,13,14). Quality systems at a contract testing laboratory should be compatible with the level of compliance the contractee requires for the work to be outsourced (e.g., research, GLP, or GMP).

Facilities and Equipment: An inspection of the contract laboratory’s facilities conducted in an on-site visit can provide much information about its operation. GMP requirements associated with manufacturing facilities also apply to laboratory areas (15). It is important to evaluate access and security of the building; design, cleaning, and maintenance of the laboratory; computerized systems; utilities; and pest control. Particular attention should be paid to equipment and lab design:

- Is the equipment validated, and is it being calibrated according to schedule?

- Are reagents being used within their expiry and discarded if expired?

- Are laboratories clean, uncluttered, and of sufficient size?

Personnel Training: Documents addressing staff training should be examined too. Is there evidence that the staff have received appropriate compliance training (GLP, GMP)? Is frequency of retraining stated in SOPs, and does the company adhere to it? Are the operators who perform the analytical methods of interest sufficiently educated, trained, and experienced in those techniques? Are there sufficient numbers of trained operators to conduct the testing? If contractors are hired to perform GMP tasks (e.g., calibration, maintenance, and cleaning), then are they trained, and is their training documented?

Method Qualification (Verification and/or Validation)

Once a contract testing laboratory has been given “approved” status, the actual methods to be used may be qualified for their purpose. If the contractor has a desired compendial method in place, the contractee is responsible for providing a sample of test material for verification according to compendial requirements. The US Pharmacopeia includes guidance on verification of compendial procedures (16). For noncompendial lot-release methods (e.g., viral and mycoplasma testing, which are driven by US FDA points to consider and ICH guidance documents), the methods will require validation if used for GMP purposes.

Validation is normally performed by a contract testing organization with a generic sample matrix, so it should not be confused with the product-specific qualification described below. Validation of compendial procedures is outlined in the US Pharmacopeia (17) as well as the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) (18). A contractee may wish to confirm the status of a given method by evaluating validation reports during an on-site visit. Contract testing labs may also be willing to provide copies of method validation reports or summary documents describing those results.

Commercial product lot release testing is expected to be performed using methods deemed suitable for a given product. This typically entails product qualification for the analytical method and evaluation of possible matrix interference. The contractee is responsible for commissioning such studies before routine use of any method and should maintain the resulting reports as evidence that the methods being used are suitable for their purpose. Such studies may need to be repeated if the processes involved in manufacturing a commercial product are modified significantly.

Quality and Business Agreements

Regulators expect that the relationship between a product sponsor and its contract testing partner be formalized by a quality agreement (7,8). Such agreements specify explicitly the responsibilities of each partner and provide the means by which a contractee extends its QC testing standards to a contractor. The agreement should list technical and/or quality contacts (names and phone numbers) at the contract testing organization as well as contact information for appropriate decision makers at the contractee organization.

Among the specifics to be detailed in a quality agreement are

- the types of compliance to be followed in contracted studies

- details on interactions between the contractor’s and the contractee’s quality systems

- requirements for equipment and assay validation, verification, and/or qualification

- assurance of quality and reporting requirements

- data recording and archiving practices

- conduct of investigations into nonconformances, deviations, unexpected, and OOS results (and timing of client notification)

- notification of regulatory inspection

- requirements for use of subcontracting laboratories

- use of debarred personnel

- availability of the contract testing laboratory for periodic technical and compliance as well as for-cause audits.

Business requirements should be addressed in a separate document and may take the form of a master service agreement, an agreement of scope, a pricing agreement, or a standard terms and conditions agreement supplied by the contractor. Such considerations may include assay pricing (including discount structures), assay initiation and report turn-around times, testing volume and exclusivity, availability of rush service and associated charges, and (in some cases) penalties for late reporting. These business agreements often specify the requirements of a contract testing laboratory with respect to contractee notification of impending sample submission, which are detailed below.

Sample Scheduling and Submission

Once a pharmaceutical company has put in place a qualified or verified method at an approved contract testing laboratory and set in place the appropriate confidentiality and quality agreements, it is free to routinely avail itself of the laboratory’s services. To optimize this partnership, and in some cases satisfy the conditions of the business agreement, a contractee must provide timely and accurate information to the contractor. Such information may include advance notification of impending sample shipment dates, sample types, and numbers (how many samples, for which assays, and so on). This enables the contractor to plan laboratory activities accordingly and ensure availability of required reagents and raw materials.

Sample submission should be in accordance with a contractor’s requirements. Typically, each contract testing laboratory will provide its own sample submission form with fields for test sample identification and login information, specific assays to be performed, assay turnaround times required (if not dictated by the business agreement) the sponsoring organization’s contact information, purchase order or contract number, and additional information needed to process a sample. Questions concerning these forms should be addressed in advance of an actual sample ship date: A contractee’s failure to complete required fields may delay assay initiation. In some cases, contractors may use electronic submission processes, which are put in place to expedite test sample submission and login, but may require some client training in use of the on-line systems. A contractee can typically arrange for such training through the vendor account manager.

The mode of sample shipment (ambient, refrigerated, or frozen with dry ice or liquid nitrogen) may be dictated by the contract testing laboratory on the basis of certain assay requirements. Contractees are responsible for validation and monitoring of temperature and shipping conditions. Required evidence of those conditions (e.g., visual inspection on arrival, use of an automated temperature recording device) should be requested from the laboratory’s receiving department as part of its confirmation of sample receipt.

In most cases, the result specification for a given test material and assay is incorporated into a method protocol or compendial procedure. Otherwise, part of the sample submission process should include informing the contract laboratory of test result specifications for a test sample and assay. It can be achieved through several means, but communicating the result specification is important to the contractor. In the absence of that, a testing facility may be unable to determine whether a given result is OOS and may be unable to comply with contractee requirements for timely sponsor notification and initiation of the required investigation activities.

In-Life Guidance and Investigation Oversight

During the in-life portion of a contracted study, the contact person (or a suitable designee) from the sponsoring organization must be available to the contractor’s study staff in case input is needed. An important example might be in the decision to terminate or continue an ongoing study in the event of an unplanned deviation or nonconformance.

Oversight of investigations is another important responsibility of the contractee. Investigations may be initiated by a contract testing laboratory during the in-life stage of an assay because of an unexpected or OOS finding, or they may be initiated at the conclusion of a study after attaining its final result. The FDA guidance on OOS results clearly states the expectations of contractee participation in investigations of such results observed at contract analytical laboratories (19). In addition, for cases in which failed product batches have been distributed, investigations may lead to filing a field alert report (FAR) or biological product deviation report (BPDR). Because the timing of such reports is outlined in guidance and regulation (20, 21), it is critical for a contractee to be promptly notified of OOS investigations at a contract testing laboratory.

The contractor must follow internal procedures for initiating an investigation and for completion of a preliminary investigation. If, however, no reason is found during the initial phase to invalidate a given study, the investigation must proceed — and it is the contractee’s responsibility to provide oversight into an extended investigation. Such oversight might include participating in design of investigation activities, providing additional samples, providing relevant data, and possibly conducting a for-cause inspection.

Contract Lab Monitoring

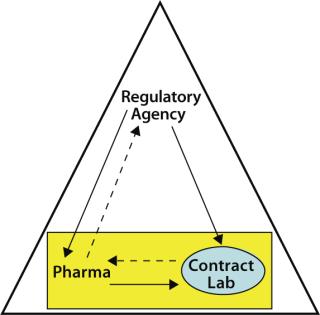

An important aspect of outsourcing QC testing by a sponsor organization includes the ongoing monitoring of the contractor by the contractee. Such monitoring is expected by regulatory agencies (8) in keeping with the philosophy that a contracted testing laboratory is an extension of the sponsor’s internal QC group. As Figure 1 shows, monitoring the contract laboratory is the contractee’s responsibility, whereas both the sponsor and its outsourcing partner are under the overall monitoring scrutiny of the regulatory agencies.

Monitoring can be performed by various means. It may consist of comparing a contractor’s performance with business and quality agreement requirements, measuring the contractor’s performance during regulatory agency inspections and periodic audits conducted by the contractee, and trending assay performance (results obtained for critical raw materials and product lot release testing; assay invalid rates; unplanned deviations and nonconformances; investigations, and so on). Ongoing monitoring can help identify (at an early stage) potential problems that may lead to unwanted delays in raw material or product testing performed at a contract testing lab.

A Good Starting Point

A pharmaceutical company’s use of a contract testing laboratory to fulfill some or all of its QC testing obligations does not absolve the sponsor of its overall quality responsibility for ensuring the safety, purity, identity, efficacy, and potency of its products. In this partnership, each partner has definite responsibilities. Here we focus on the major responsibilities of the contractee. This should be considered a starting point for defining and formalizing a robust and defensible contract testing laboratory administration and oversight process, but it should not be construed as the final or definitive word. As always, the regulatory agencies themselves provide the ultimate guidance.