Personalized medicine is a catch phrase of the 21st century — and with good reason. Advances in genetics and biochemistry promise to tease apart factors that explain why some patients benefit dramatically from a therapy whereas others receive no benefit at all. They also help explain side-effect profiles.

To accomplish such lofty goals, drug makers are increasingly partnering with diagnostics companies to develop companion biomarkers. But these companies operate in very different business and regulatory environments, so partnerships can be complicated by contrary goals and misunderstandings. Before entering such a relationship, each participant should understand a potential partner’s world view and economic incentives, as well as recognize potential difficulties.

Seven QuestionsHere are seven questions for biopharmaceutical companies to consider when evaluating a partnership with a diagnostics company.

Do you understand the value proposition? Companion diagnostics both enable and limit opportunities. They can benefit patients by identifying those most likely to respond positively to a drug without side effects. Diagnostics can help clinical investigators select patients who are most likely to produce cleaner data, thereby reducing sample sizes (and development costs). A product’s market size might increase if a diagnostic identifies suitable patients who are receiving a competing drug. A diagnostic may rescue a drug candidate that could otherwise fail.

But companion diagnostics may limit opportunities by eliminating otherwise prospective patients, potentially reducing a product’s market share. So biopharmaceutical companies must weigh advantages and disadvantages when deciding whether to pursue a companion diagnostic.

The balance of advantages and drawbacks is typically favorable when a drug meets two criteria:

-

The drug is appropriate for an identifiable subset of a disease population.

-

Physicians are unlikely to prescribe the drug without the diagnostic because of cost, side effects, or other reasons.

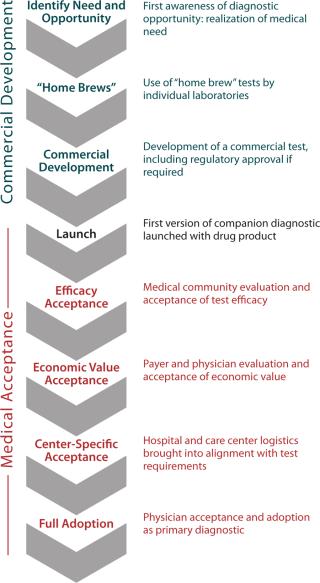

Have you considered all the adoption hurdles (Figure 1)? Companion diagnostics add to up-front research and development costs before their utility is proven. At product launch, a diagnostic’s science and technology may not yet enjoy the same confidence level as a drug would. The true relevance of chosen biomarkers to clinical outcomes may be considered indirect and not entirely predictive. Even if a test is ready, the market may be reluctant to immediately accept it. Convenience, cost, and speed may not yet be optimized. Hurdles to diagnostics adoption differ around the world. Not every country has the same infrastructure or willingness to pay for some diagnostics.

Is there enough market competition for your diagnostic (and why is this essential to your success)? Biopharmaceutical companies should foster competition among diagnostics companies. Wedding a drug to a single diagnostic platform can be a bad idea. A single diagnostic’s cost, reliability, and clinical utility are central to its success. Monogram Biosciences (www.monogrambio.com) created and focused on maximizing the value of a companion diagnostic for Pfizer’s Selzentry HIV drug. The expensive Trofile diagnostic was crucial for FDA approval, despite its considerable lag time between testing and results. Analysts predicted it would limit the drug’s market receptiveness.

It is difficult to predict what a final diagnostic will look like or how expensive it will be at product launch. But a diagnostics company will be focused on the value of its product, as Monogram demonstrated when it announced the unexpectedly high price for the Trofile test. Early development of competing diagnostics would have limited the company’s market power.

If a diagnostic winds up on a drug’s label, it should be reasonably priced and reliable. Physician resistance for any reason can negatively affect a drug’s success. Genentech’s Herceptin monoclonal antibody is another example, having been somewhat victimized by a diagnostic with questionable accuracy (based on fluorescence in situ hybridization).

How do the perspectives and motivations of the diagnostics company differ from yours? Diagnostics companies’ business models differ significantly from those of drug makers. Although some diagnostics companies are affiliated with large corporations, most are usually not well capitalized, making them more risk averse and less likely to embark on prospective clinical trials or enter emerging markets without some degree of certainty. Such companies may demand financial investment from potential partners or insist on fee-for-service agreements. Diagnostics companies also are trending toward developing intellectual property around their tests or otherwise retaining rights after product launch in hopes of creating long-term revenue drivers.

With the increasing value of diagnostics, these companies are pursuing both short- and long-term revenue goals. Pharmaceutical companies see “drugable” targets and pursue multiple pathways to unlock their value; a diagnostics company typically leverages a single technology platform across multiple applications. To minimize technology and market risk, biopharmaceutical companies should ally with several diagnostics companies (or a single large company) to pursue multiple biomarkers and technologies.

Does your regulatory team appreciate that diagnostics companies play by different rules? Diagnostics face a much lower regulatory burden than drugs and have shorter life cycles. Some tests require no FDA approval, are launched with less supporting clinical data than physicians and payers are accustomed to seeing for drugs, and often are not reimbursed. So the medical community may be skeptical if costs are high, convenience is low, and false test results are frequent. It can take up to a decade or more to achieve widespread use of a new diagnostic product.

Will managed-care or central payers pay for your test? Diagnostics are not always covered by insurance companies, which typically insist that products directly contribute to better outcomes to be reimbursable. From the insurer’s perspective, a diagnostic must create value, often by screening patients to prevent inappropriate treatment and reduce costs. The more expensive a test is, the greater its cost savings must be to justify the expenditure.

Recent genetic diagnostics offerings prov

ide users with risk profiles related to various conditions such as heart disease or cancer. Patients may find such tests interesting and useful for taking control of their own preventive measures, but insurers will not cover tests that do not dictate treatment decisions.

Diagnostics are seldom supported by much published clinical evidence at the time they are introduced. Insurers want published studies to demonstrate clinical utility. So they are often left to make decisions with what imperfect information is available.

Is this a “one size fits all” market? Not every physician has the same expectations of a diagnostic test. Type 1 (false positive) and type 2 (false negative) errors are important concerns. Some doctors require accuracy at all costs and will wait days or weeks to avoid false positives. Others need quick results and accept higher rates of inaccuracy. It is important to consider the consequences of false positives (increased expense, potential side effects with powerful therapeutics) and false negatives (untreated and inappropriately treated patients) and use or design appropriate diagnostics. Physician preferences play a role: Doctors weigh test results, costs, medical risks, and convenience. Those with patients at immediate risk of a condition will have no use for a test with a high rate of false negatives, regardless of cost and convenience. But they might accept a high false-positive rate if the safety risk and cost of the accompanying treatment are comparatively low.

TYPES OF DIAGNOSTICS AND THEIR REGULATIONMolecular diagnostics fall into three general categories: test kits, laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), and in vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays (IVDMIAs). The latter two are sometimes referred to as “home brews.”

Test Kits are made and marketed for any laboratory to use. Their process of specimen collection, testing, and results analysis can be performed in many settings. Examples include pregnancy tests, flu tests, allergy tests, and breathalyzers. In the United States, test kits are regulated by the US FDA.

LDTs are analyzed only by the proprietary laboratories that develop them, although specimen collection can be performed anywhere. Genentech’s HER2 diagnostic falls under this category. Most LDTs are not FDA-regulated, but testing laboratories are usually inspected for safety by clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIAs) of the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. LDTs usually get to market quickly but may carry a credibility stigma due to the absence of regulation. Rapid proliferation of competing LDTs cannot be controlled by the pharmaceutical company that commissioned the original. Genentech has petitioned the FDA for regulation of LDTs in an attempt to clear the market of poor-quality HER2 diagnostic tests.

IVDMIAs require proprietary, complex mathematical algorithms to analyze their results, so physicians cannot interpret those results directly. An example is XDx, Inc.’s (www.xdx.com) AlloMap test, which is used to manage potential for organ rejection in heart transplant patients. IVDMIAs are frequently LDTs, but in the United States they are FDA-regulated.

EU Diagnostic Regulation: Companion diagnostics are generally governed by the In Vitro Diagnostic Directive (IVDD 98/79/EC) published in June 2000, with mandatory compliance enacted December 2003. This applies to medical devices that are reagents, reagent products, calibrators, control material, instruments, kits, apparatuses, equipment, or systems intended to be used in vitro for assessment or to examine blood and tissue donations of human origin for gathering information. Under IVDD, conformity assessments are carried out by ~25 “notified bodies” designated by the various member states of the European Union.

Due DiligenceCompanion diagnostics must be viewed with a broader understanding of the diagnostics environment. Consider the value a diagnostic can bring to your drug. Will it increase or decrease your product’s market share? Make certain that the test developed is in line with physician and payer needs and disease characteristics. In the early stages of clinical research, conduct exploratory studies with companies using a range of platforms before selecting the most promising one(s) for further development.

Author Details

Richard Tinsley is a partner at Putnam Associates, a healthcare strategy consulting firm headquartered in the Boston, MA, area and founded in 1988 to serve the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, diagnostics, and medical device industries globally; 1-781-273-5480; rtinsley@putassoc.com;