Allen Roses, former worldwide vice president for genetics research and pharmacogenetics at GlaxoSmithKline, raised eyebrows in 2003 when the newspaper The Independent quoted him as saying that the vast majority of drugs — more than 90% — work in only 30 or 50% of the people. “I wouldn’t say that most drugs don’t work,” he said. “I would say that most drugs work in 30 to 50 percent of people.”

Though the newspaper characterized this as an “open secret within the drug industry,” it said that the declaration was the first time a senior executive within the industry had stated so publicly. Given individual genetic variance and the differing molecular mechanisms underlying diseases, as much as US$350 billion a year (by some estimates) are wasted on ineffective medications. In simple terms, many classes of drugs are ineffective on a large percentage of the patients for whom they are prescribed.

In the past 10 years we’ve experienced radical changes in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries in how drugs are developed, how companies are funded, and what constitutes value. We are in the midst of a dramatic transformation in health care driven by technology, patients, payers, and providers. And while the pharmaceutical industry is struggling with a host of issues from patent expirations to problems with R&D productivity, the biotech industry continues to prove itself as a rich source of high-value innovation.

The Human Genome Project, the multibillion dollar international public–private effort that produced a completed map of the human genome in 2003, promised to change the very problems that Roses spoke about. The original expectation was that the information we would eventually tease from our new understanding of the genetic make-up of individuals would enable doctors to deliver the right drug at the right dose to the right patient at the right time. This also would move medicine away from being reactive toward becoming more personal, preventive, and predictive.

The complexity and cost of translating our new-found understanding of the genome into diagnostics and therapies has tempered enthusiasm about the genomic revolution, leading some people to question whether we’ve yielded anything meaningful from the massive investment made in cracking the genetic code. But despite the frustration with the pace of development of a new era of genomic medicine, the reality is that the revolution is well under way. New personalized medicines approved in 2011, such as Pfizer’s lung cancer drug Xalkori and Roche’s melanoma drug Zelaboraf, are delivering on the promise. They also represent a dramatic shift within the pharmaceutical industry.

Consider Pfizer’s Lipitor statin, the best-selling drug of all time. It was late to the party, the fifth statin to reach the market. Arguably, a drug maker today faced with the decision to make a large investment in clinical development to bring such a drug to market would be unlikely to do so under the circumstances. But the Lipitor product stands as a symbol of success in the one-size-fits-all blockbuster model that defined an era in which marketing muscle and large sales forces drove drug sales.

Today, pressures created by the pharmaceutical industry’s patent cliff are intense. Drug companies have shed not only sales employees, but also workers across the board. They have sought to replace revenues lost to generics competition by moving in all directions: acquiring competitors, moving into over-the-counter products, and even turning to selling generic drugs themselves — particularly as the potential for sales growth in emerging markets outshines anemic growth in developed markets of the United States, Europe, and Japan.

Pfizer’s statin, which had peak sales in excess of $13 billon, is now facing competition from generic versions. The same is true for the other one-size-fits-all blockbusters that made up the list of best-selling drugs in 2002. By 2016, that same list will be dominated by biologics, with EvaluatePharma projecting that they will make up seven of the top 10 drugs by sales and 45 of the top 100. Names such as Humira, Rituxan, and Herceptin will top that list (1).

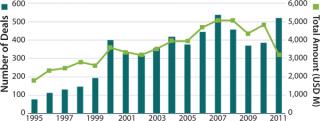

As drug makers seek to bring new products to market, they must now do so in an environment in which payers demand that drugs not only be safe and effective, but also demonstrate evidence of value. As many of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies cut their R&D operations, they are increasingly seeking external sources of innovation to achieve cost-effective progress. They are engaging in partnerships with academic institutions that would have been unheard of a decade ago, licensing agreements with biotechnology companies, and pursuing acquisitions to purchase novel products outright (Figure 1).

That’s good news for biotechnology, which continues to be an important source of innovation for the pharmaceutical industry. An astounding reminder of the biotech industry’s ability to create value could be seen in the 2009 acquisition by Roche of the portion of Genentech it did not already own. The deal valued Genentech at US$100 billion, at the time more than the entire value of Pfizer, which was then the world’s largest pharmaceutical company.

In 2011, the value created by biotech could be seen in deal after deal. Whether it was Sanofi’s $20.1 billion acquisition of Genzyme, Takeda’s $13.7 billion acquisition of Nycomed, Gilead’s $11 billion acquisition of Pharmasset, or Teva’s $6.8 billion acquisition of Cephalon, the biotech industry has been a source of value creation.

At the same time, biotech has become increasingly dependent on the pharmaceutical industry as a source of not only funding, but also distribution muscle. Ten years ago, young biotech companies may still have envisioned becoming fully integrated companies with venture investments leading to initial public offerings. Today, instead of seeking to build companies, venture investors are limiting their risks by funding experimental therapies through proof-of-concept, at which point they can then license or sell them.

Although the changes we’ve seen in the past decade have been dramatic, they will accelerate at a blinding pace in the decade ahead. The convergence of information technology, ubiquitous wireless connectivity, and low-cost monitoring will allow people to gather endless amounts of real-time data about their own health and bring about the type of personalized, predictive, and preventive medicine envisioned when the human genome project began.

This new world of digital health is changing the way people access and deliver care. Telemedicine is connecting specialists in large urban centers to patients at remote rural clinics. Seniors are able to live independently for many more years thanks to monitoring technologies that alert providers to health problems before they require costly hospitalizations. And wireless sensors are helping to ensure compliance with drug regimens and help keep patients on track. Real-time monitoring is providing feedback so people can better manage chronic disease. And games and social networks are helping to change unhealthy behavior and encourage lifestyle improvements that benefit health. These changes are placing patients at the center of health care and putting consumers in greater control of their own health.

Low-cost sequencing, now upon us, will allow scientists to grasp the role genetics plays in disease and begin to unravel the interactions of genes, the proteins and bacteria in our bodies, and our diets and environment. Electronic health records are producing a rich source of information ready to be tapped to provide new insights into public health and the most effective treatments. And new in-home monitors and smart-phone–enabled digital health applications are providing a stream of data ready to be analyzed for insights into our individual states of health and wellness.

The biggest challenge will not lie in chemistry or biology, but rather in turning this flood of data into meaningful information that can unravel the underlying causes of disease, provide insight into safe and effective treatments, and provide early warnings and even preemptive warnings to keeps us healthy.

For those of us who invest in the biotechnology sector, valuations are historically attractive, and power at the negotiating table lies with those who have capital. The opportunities before us have never been greater. The need for innovations that can bend the cost curve on health care through new ways of access and delivery, improve the efficacy of drugs, and meet unmet medical needs is being felt around the world. The life sciences provide not only a solution, but a way for countries around the world to build innovation-based economies.

That’s good news for biotechnology, which continues to be an important source of innovation for the pharmaceutical industry. An astounding reminder of the biotech industry’s ability to create value could be seen in the 2009 acquisition by Roche of the portion of Genentech it did not already own. The deal valued Genentech at US$100 billion, at the time more than the entire value of Pfizer, which was then the world’s largest pharmaceutical company.

In 2011, the value created by biotech could be seen in deal after deal. Whether it was Sanofi’s $20.1 billion acquisition of Genzyme, Takeda’s $13.7 billion acquisition of Nycomed, Gilead’s $11 billion acquisition of Pharmasset, or Teva’s $6.8 billion acquisition of Cephalon, the biotech industry has been a source of value creation.

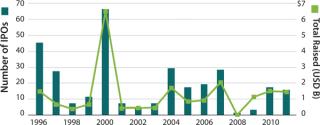

At the same time, biotech has become increasingly dependent on the pharmaceutical industry as a source of not only funding, but also distribution muscle. Ten years ago, young biotech companies may still have envisioned becoming fully integrated companies with venture investments leading to initial public offerings. Today, instead of seeking to build companies, venture investors are limiting their risks by funding experimental therapies through proof-of-concept, at which point they can then license or sell them.

Although the changes we’ve seen in the past decade have been dramatic, they will accelerate at a blinding pace in the decade ahead. The convergence of information technology, ubiquitous wireless connectivity, and low-cost monitoring will allow people to gather endless amounts of real-time data about their own health and bring about the type of personalized, predictive, and preventive medicine envisioned when the human genome project began.

This new world of digital health is changing the way people access and deliver care. Telemedicine is connecting specialists in large urban centers to patients at remote rural clinics. Seniors are able to live independently for many more years thanks to monitoring technologies that alert providers to health problems before they require costly hospitalizations. And wireless sensors are helping to ensure compliance with drug regimens and help keep patients on track. Real-time monitoring is providing feedback so people can better manage chronic disease. And games and social networks are helping to change unhealthy behavior and encourage lifestyle improvements that benefit health. These changes are placing patients at the center of health care and putting consumers in greater control of their own health.

Low-cost sequencing, now upon us, will allow scientists to grasp the role genetics plays in disease and begin to unravel the interactions of genes, the proteins and bacteria in our bodies, and our diets and environment. Electronic health records are producing a rich source of information ready to be tapped to provide new insights into public health and the most effective treatments. And new in-home monitors and smart-phone–enabled digital health applications are providing a stream of data ready to be analyzed for insights into our individual states of health and wellness.

The biggest challenge will not lie in chemistry or biology, but rather in turning this flood of data into meaningful information that can unravel the underlying causes of disease, provide insight into safe and effective treatments, and provide early warnings and even preemptive warnings to keeps us healthy.

For those of us who invest in the biotechnology sector, valuations are historically attractive, and power at the negotiating table lies with those who have capital. The opportunities before us have never been greater. The need for innovations that can bend the cost curve on health care through new ways of access and delivery, improve the efficacy of drugs, and meet unmet medical needs is being felt around the world. The life sciences provide not only a solution, but a way for countries around the world to build innovation-based economies.

Author Details

G. Steven Burrill is CEO of Burrill & Company and author of Biotech 2012: Innovating in the New Austerity. Burrill & Company, One Embarcadero Center, Suite 2700, San Francisco, CA 94111; 1-415-591-5449; sburrill@b-c.com; www.burrillandco.com.

REFERENCES

World Preview 2016: Beyond the Patent Cliff