Life sciences company leaders need to put the right people, processes, and technologies in place to create evolutionary cultures. Such cultures would embrace advanced manufacturing process intelligence and reap related business benefits. Since the late 1990s, my software company has helped biomanufacturers improve their process understanding. In that time, we’ve seen regulatory drivers such as quality by design (QbD) and process analytical technology (PAT) guidances call for improved manufacturing process performance through better process understanding and optimization.

We define process intelligence as the technology and systems needed to design, commercialize, and sustain robust manufacturing processes that provide predictable high-quality outcomes cost-effectively based on scientific process understanding. Through our experiences, we see three key elements helping successful companies reach an advanced level of process intelligence: people, processes, and technologies. Combined correctly, those three components create a process intelligence culture that evolves through distinct levels of advancement.

PRODUCT FOCUS: ALL BIOLOGICS

PROCESS FOCUS: MANUFACTURING

WHO SHOULD READ: OPERATIONS, PROCESS MANAGERS, DATA ANALYSTS

KEYWORDS: INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, QBD, STAFFING, COST MANAGEMENT, HUMAN RESOURCES

LEVEL: INTERMEDIATE

Drawing from “Management 101” lessons, we know that when our customers’ leaders foster cultural change by empowering people and leveraging the right business processes and technologies, organizations reap greater, measurable rewards, including risk reductions, faster times to market, and greater operational efficiencies. Business teams need to drive organizational change before information technology (IT) experts can implement solutions that are measured on their business value.

The Road to Advanced Process IntelligenceAccording to Gartner’s 2012 survey, 56% of organizations have insufficient visibility into manufacturing (Figure 1). Resulting symptoms of poor process control include product recalls, lost batches, and quality problems (1).

Manufacturers that recognize the potential benefits of a process intelligence culture can emulate the best practices of admired companies. Customer insights and case studies informally gathered over the past decade provide insights into how forward-thinking life sciences companies shift their cultures to adopt manufacturing process intelligence as a way of life. Such companies — and there are only a handful who can truly claim this — describe their “advanced process intelligence” cultures as an ongoing desired state. Their best practices relate to people, processes, and technologies, including

-

empowering people with information, expectations, and responsibility and holding them accountable (management included)

-

aligning goals and objectives across groups and divisions whenever possible and communicating them repeatedly

-

creating a collaborative, open environment across traditional corporate “silos” and using technology tools for information and data sharing.

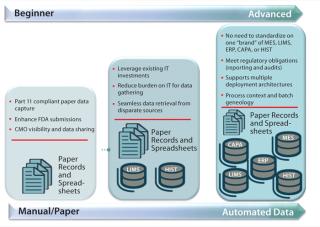

Such companies share manufacturing science–driven cultural norms, value innovation, and turn to technology for enablement. Figure 2 illustrates a continuum that categorizes automation and data infrastructure maturity. Early, intermediate, and advanced cultural characteristics are described below.

Companies that possess a “readiness” for process intelligence recognize that they need better process models based on relevant professional experience and on data from small- and large-scale experiments to reduce variability and improve productivity and quality. They typically have no formal processes in place for data collection and analysis — with more reactive responses to batch failures using spreadsheet methods. To enter the earliest levels of the process intelligence cultural continuum, selected members of a manufacturing organization must recognize that they need better ways to collect and access reliable supporting data for investigations and understand and champion potential benefits of better process understanding. That can be achieved through

-

meeting regulatory requirements more efficiently and contributing to regulatory guidelines for PAT, QbD, and stage 3 process validation

-

speeding time to market for new products

-

improving product quality outcomes

-

reducing process variability

-

establishing collaboration among process development, manufacturing, and quality teams.

Such “early” stage companies — regardless of size — engage in internal discussions to tackle several difficulties. Problems might include upper management and IT departmental buy-in and endorsement; putting technology and tools in place for efficient data access and sharing; enabling effective, data-centric collaboration across sites and company divisions; and putting QbD initiatives in place. Those companies often struggle with paper-based process data records and spreadsheets and with breaking down organizational silos, encountering reluctance to changes or upgrades in their IT systems.

Part of cultural advancement requires assessing the necessary people, processes, and technologies. Relying on process development or manufacturing contractors can introduce variability. So experienced companies recommend having a well-thought-out plan in place for how to get management buy-in for the required level of intimacy with contractors. One life sciences compa

ny built its business case for process intelligence investment through a risk assessment on 12 of its products. It found that its highest risk was lack of product understanding. Its senior team included anchor statements in its four-year strategic plan to be “right the first time” and limit process deviations. The performance statements stretched the company’s limits to take specific actions that would advance process intelligence.

Authors of a recent McKinsey Quarterly article encouraged measuring employees’ and managers’ success based on their contributions to long-term organizational health as much as on performance. According to the authors, “The fact is that when people don’t have real targets and incentives to focus on the long term, they don’t. Over time, performance declines because not enough people have the attention, or the capabilities, to sustain and renew it” (2). Companies in the important early stage of a process intelligence culture need to adopt a similar long-term view that maps their road to advancement.

Intermediate Stage: People, Process, and Technology Resources in PlaceCompanies advancing their data infrastructure on the process intelligence continuum typically invest in technology tools to capture electronic records. People better collaborate across departments and manufacturing sites for batch comparisons and knowledge sharing. Such companies also monitor process critical quality attributes (CQAs) and key performance indicators (KPIs) for predictive insight. When deviations occur, these companies have specific starting places and business processes in place for investigations.

Real-world examples illustrate different expansion approaches. Some companies implement new systems and practices in just one division (such as process development) and then move to manufacturing. Others start with one manufacturing site and later expand to others. A few have implemented a product- or risk-based approach across manufacturing sites to prioritize plans. One company, for example, currently has 600 control charts in place for monitoring a single group of related processes and plans to begin multivariate analysis using its aggregated data. The common denominator is that all these companies have gained sufficient process understanding for a portion of products and are engaged in leveraging all available data to make informed business decisions.

Defining business processes is a frequent challenge at this data-rich, intermediate stage. Working through change management typically includes examining all business rules and requirements. How can analytics be applied to influence processes and business decisions? Will Western Electric or other rules be used to determine “in-control” states before they are rolled out to the organization on a larger-scale?

We see champions within these companies presenting tangible examples of their “wins”: enhanced productivity, time and cost savings, reduced variability, improved yields, and fewer lost batches. Better understanding and communication both map to positive effects on the bottom line that encourage further manufacturing process intelligence culture advancement.

Advanced: Process Intelligence across Manufacturing NetworksThe few companies with advanced manufacturing process intelligence cultures share common characteristics across process development, manufacturing, quality, and IT. Such companies

-

leverage process data for enterprise-wide decision-making at multiple sites to better understand sources of variability, achieve process predictability, and ultimately improve yields across manufacturing networks

-

implement QbD initiatives and continuous process improvement systems with sufficient process understanding across all sites and processes

-

provide data-centric collaborative teams with tools to capture data and put it into action across sites and company divisions

-

leverage business intelligence proactively based on process intelligence data

-

obtain management buy-in and endorsement at the highest levels.

These companies strive for similar visions of understanding every product and process to a sufficient level throughout their manufacturing networks, including the contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) with which they work. Visibility and transparency based on actual data are key infrastructure elements for advanced manufacturing process intelligence. For example, one company installed large flat-screen monitors on its manufacturing plant walls, along with dashboards on desktops, to enable proactivity throughout its organization — from upper management to the shop floor. Its teams meet regularly to review reports across department silos, so they see trends before issues arise and proactively solve problems before processes are out of specification limits. Internal quality and regulatory groups interact, and special teams are assigned to investigate as needed.

Advanced companies agree that when teams share data that puts them “on the same page,” quality becomes everyone’s job, and multiple departments can own process evaluation and improvement. This leads to a desirable, science-based culture that thrives on innovation. With the right capabilities in place, some companies innovate in directions they never expected, such as monitoring manufacturing equipment energy usage.

One company generates charts updated on a Microsoft SharePoint site to expose information throughout its organization. Quick, visual comparisons are checked each morning to see where collaborative team efforts can be focused. The company uses quantitative analysis with comparisons by categories (e.g., raw material lot numbers) to show the effects of variable changes with plotted control charts. Reviews of easily prepared chromatogram overlays quickly show peaks that don’t belong (compared with a golden batch). Seeing a picture of exceeded limits helps teams better understand process trends. For technology transfer, these practices enable easy site-to-site comparisons with CMOs — showing graphs that indicate concerns where curves diverge. Advanced process intelligence cultures are driven by “data scientists,” whose roles are to bring data management, analytics, modeling, and business analysis together through technology as Gartner describes in Figure 3.

In a March 2012 paper (3), Gartner authors explain:

Culturally, we obse

rve many organizations, either as a whole or in specific business units, gravitate toward being ‘fact-oriented’ rather than ‘supposition-oriented.’ This is based on the availability of new data sources and a new breed of business professional raised on a steady diet of data, but also on marketplace volatility and competitive flux — which demand faster and more continuous decision making abilities. Data science is a key enabler of fact-based, decision-oriented business processes.

In advanced process intelligence cultures, data infrastructures make all users better data scientists. They can collaborate with easy-to-use technology and processes that don’t get in the way of what they are trying to accomplish, whether it’s quickly identifying the root cause of a problem for appropriate corrective action or optimizing everyday decision making.

Insights to Cultural EvolutionA company can’t simply hire new people, implement new technologies, mandate new processes, and expect change. Volumes of content can be found on guiding cultural evolution, but some key insights from companies that live and breathe best practices are useful.

As Amgen’s Chris Pacheco stated in a recent BioProcess International article, “Approaching [manufacturing] improvements with a focus on learning from others coupled with the speed of sharing to accelerate learning is driving a positive transformational shift in the manufacturing facility’s culture” (4).

To inspire cultural change, many experts suggest creating a shared vision and modeling new behaviors to make them a reality. Most of the visions we’ve seen over the past decade were inspired by regulators’ guidelines for QbD initiatives and PAT and economic pressures that called for better process understanding to prevent costly lost batches and improve product yields. Encouraging a science-based culture and institutionalization of knowledge is key to delivering what the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is requesting.

If there were simply a cut-and-paste “checklist” for advancing a process intelligence culture, more companies would find themselves at the most-advanced end of the continuum. Instead, getting there requires a road of adaptation with the right elements in place across organization chart layers, department silos, and geographical boundaries. Process intelligence is a process itself — which, like a vision — will be approached over time, so it demands an agile culture.

On that journey, new people will come into the organization, and processes and technologies will be introduced that require thought and flexibility. However, new people tend to see an organization’s culture as existing, so documenting and standardizing can ensure that the long-term vision moves toward advanced manufacturing process understanding across global manufacturing networks within the context of the company’s capabilities and opportunities. The vision must be shared, bought into, and used as an incentive and metric for realistic action plans that leading companies have modeled for the rest of the industry to emulate.

Author Details

Justin Neway, PhD, is founder, vice president, and chief science officer of Aegis Analytical Corp. (now part of Accelrys, Inc.), 1380 Forest Park Circle, Suite 200, Lafayette, CO 80026; 1-303-625-2100, fax 1-303-926-1161;