One response to a survey we sent out last year kept coming back to me as we prepared this issue. In answer to what a company does if a product in development doesn’t fit into the company’s platform technology, one answer was, “We innovate a solution.” Whether meant seriously or not, it rings true to the history of the industry’s ability to invent and reinvent solutions as necessitated by economic realities.

When we began working on the topic of this special issue, we thought we knew the trends and would simply be offering examples of the burgeoning of “local” manufacturing around the world. We assumed that the global biotech industry had reached a sort of geographical “tipping point,” when in actuality, the choices appear to be much less clear-cut. It is true that what has in the past been accomplished by vertically integrated companies in major biotech hubs can now be done pretty much anywhere in the world. This presents companies, new and established, with a number of business models and options — but not yet a lot of cumulative experience doing business in a number of regions that are now aiming to attract the industry. We realized we needed to explore not only what those options are (or rather, how they come together), but how it is that companies sift through available technologies and related business options in the first place.

Another component of this puzzle is provided by a general theme that we noticed at the recent BIO convention, especially as I listened to the presentations in BPI’s BioProcess Theater there. Seldom have I seen so many new approaches being advanced all at once, and in such combinations, challenging even our assumptions of what biotherapeutics/pharmaceuticals will be in the future. Recombinent technologies have helped give vaccines a virtual “shot in the arm”; cell and gene therapies have quietly been proceeding through clinical trials, and with the Dendreon approval charting the path, now may have a clearer path to approval and commercialization. Combination (or convergence) therapies and personalized medicines are creating new regulatory conundrums as devices and diagnostics merge with therapeutics. And economic development groups in emerging countries see opportunities to attract business and advance their own products, with biosimilars already on the market in some regions.

Single-Use at the Forefront: We laid the groundwork for this issue by developing a roundtable discussion at the Interphex conference this past April (see the “Interphex Roundtable” box). Our speakers highlighted critical elements behind manufacturing and distribution options, pandemic preparedness, and economic realities. And yet, when the time for Q&A came around, all the questions had to do with the scalability of single-use technologies. These technologies have certainly been a “disruptive” influence on the industry, but they are not alone in paving the way for local manufacturing.

Local?

So, first, a definition: Local, in this issue, can refer to

- In-house, nonoutsourced production and/or manufacturing (and the extent to which companies are able to keep some work in-house that may have been outsourced in the past)

- Production and/or manufacturing in the specific region of eventual distribution, either as a self-contained company or as a remote subsidiary of a company headquartered in another country.

If it is “local,” it is under your control. If you intend to market to the world, and you have an established manufacturing center in your home country, then your current distribution channels may be the best choice. If by contrast you are making a therapeutic vaccine or other biotech drug for a disease or illness specific to a remote region, it may make little economic sense to produce it in, say, New Jersey — especially given potential supply interruptions in cases of political crises or outbreaks of disease.

In between those two extremes are any number of combinations of approaches — and viewpoints. And entering the field in increasing numbers are companies and agencies in the so-called developing world, advancing their own innovations and working to become global manufacturing hubs in their own right and seeking to supply their own regions with the raw materials of drug development.

Our goal in this issue is to provide a combination of anecdotal and documented viewpoints to create a clearer picture of where the industry might be headed — and what elements are still needed to “tip” biopharmaceutical manufacturing into a truly global manufacturing arena.

Surveying Our Readers

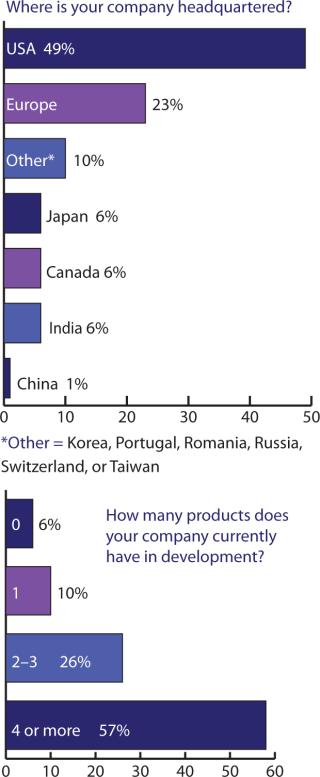

We also aproached this project, as we often do, by surveying our readers. Responses (as usual) told us much of what we expected, but created more questions. The small number of self-selected responses (77) also leads me to interpret the results overall as indicative of where BPI’s readers may generally stand on these issues, but I hesitate to draw conclusions applicable to the industry as a whole. This is also due, in part, to BPI’s circulation breakdown: We are only now actively building our circulation in the Asia-Pacific, so those readers may be disproportionally represented here. Still, it is a start, and I offer some of the results here for your consideration. As always, I welcome your comments.

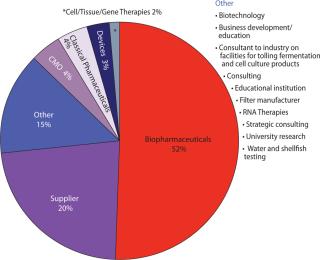

What Is Your Primary Business, and Where Are You Manufacturing? Figure 1 shows that >50% of respondents are working in “biopharmaceuticals,” which as we know encompasses a broad range of products and processes. As technologies merge, results such as these may become more and more misleading. “Devices” for example might be produced alone or in combination with a drug. A number of “biopharmaceutical” companies and even supplier companies are beginning to develop ancillary cell-therapy businesses — and so on.

Figures 234 told me somewhat what I expected, but cross-tablulating the responses indicates that something else must be pointed out: US companies may tend to keep as much as 79% of their manufacturing in the United States, with the remaining portion established (or outsourced) in Europe, the United Kingdom, and Canada. European companies, by contrast, manufacture/outsource ≤50% to the United States, keep about 38% within Europe (including the United Kingdom), with 3% of the work going to Canada and Japan — and nearly 6% to India.

INTERPHEX ROUNDABLE

Our panel discussion held Wednesday, 21 April 2010, at the Interphex convention in New York, NY, addressed geographic trends and strategic responses in biomanufacturing. The program outlined ways to translate geographic constraints into opportunities for “safer, cheaper, faster, and better biological products.”

Participants were

- Anne Montgomery, editor in chief, BioProcess International (co-chair)

- Robert Broeze, president and chief executive officer, Laureate Pharma, Inc. (co-chair)

- Jim Wilkins, chief technology officer, Sensorin

- Rahul Singhvi, ScD, MBA, president and chief executive officer, Novavax, Inc.

- Mani Krishnan, director, Mobius Downstream Processing, Millipore Corporation

- Tom Ransohoff, vice president and senior consultant, BioProcess Technology Consultants.

Panelists addressed several topics that form the subject matter of this special issue; their comments will be presented in full in a BPI special report in September 2010. They talked about how manufacturing innovations drive new business models, with a focus on ensuring access to important vaccines: How do you do that when there are no local manufacturing facilities? How does a company bring in local manufacturing, create a profit, and still address the larger social problem? If a company establishes local manufacturing, how does it assure quality and consistency from site to site? Topics included

- cross-border issues related to offshore manufacturing

- effects of disposables and other new technologies on processes, geographic decisions, and costs

- emergency preparation and distribution of vaccines

- geographic distribution of capacity (CMO proximity issues, strategies for selecting local versus distant production sites, capacity data and trends)

- international supply chain maintenance; cold-chain monitoring; and technology transfer across borders

- regulatory issues across borders and agencies

- technological changes and innovations affecting site selection and manufacturing choices, including political and tax considerations.

Biopharmaceutical companies in the United Kingdom appear to take advantage of more widespread options, with over 80% of their manufacturing going to the United States, Europe, and remaining in the United Kingdom; 31% and 37% to Canada and Japan, respectively; 44% to China; and 50% to India. What is actually being manufactured where, however, was outside the scope of this survey to determine.

Looking at this from the perspective of Indian companies, it appears that what isn’t produced within India goes mainly to the United States (60%) and then in equal portions (7%) to Canada and Europe. Companies headquarted in China appear to hold onto 8% of their manufacturing and otherwise have manufacturing facilities in the United States (68%) and Europe (25%) which indicates that they don’t work much within other countries in the Asia-Pacific. If these responses do indicate a trend, it is that manufacturing location decisions are still based largely on comfort levels with similar cultures and languages and that political/ideological divisions may influence location decisions more than eventual distribution and marketing goals.

Another element to track was introduced to me in a discussion I had at the BIO convention with the folks from Singapore. Using their development plans as one example, various agencies and consortia in regions that are already multicultural and/or multinational hubs for other, older industries are aggressively working to become centers of biotechnology innovation. One goal is to develop sources of materials and supplies specifically for Asia-Pacific regions/companies. So easing distribution costs and ensuring supply-chain availability are new and/or emerging areas of opportunity for economic development on a global stage.

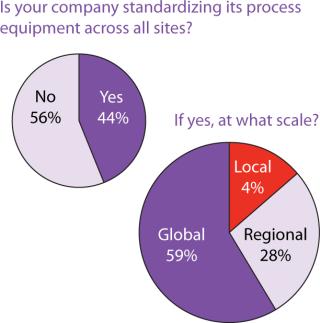

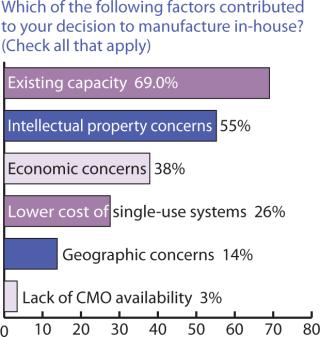

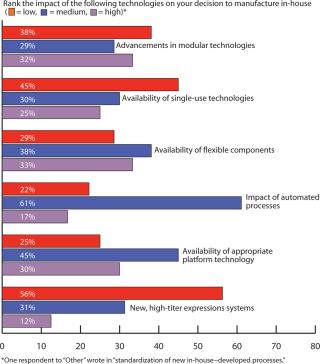

Outsourcing Plans: Although companies do have more options these days for keeping manufacturing in-house, our survey indicated close to a 50:50 split between in-house and outsourced manufacturing (Figure 6). Figure 7 indicates that capacity availability helps companies protect their intellectual property and control costs in light of enabling technologies, as ranked in Figure 8.

Oddly, responses revealed almost a 50:50 split between those who felt that a CMO’s proximity to a sponsor’s headquarters or target market was particularly important or not. A small majority ranked proximity as “somewhat important.” Major opportunities would seem to be available for CMOs to offer services in emerging regions as well as for those suppliers developing validatable units for cold-chain monitoring.

Geographic factors behind manufacturing locations include favorable cost considerations (56%), a supportive local infrastructure (51%), existing facilities in the region of choice (46%), geographic proximities to the target market (31%), and geographic necessity for emergency responses (15%). Other elements included the availability of an experience workforce, time-zone proximity to ease communications, and regulatory requirements.

Of factors that influence a company’s decision to manufacture outside of its home country, 50% cited intellectual property, other regulatory concerns and the cost of training a local workforce. Quality control of input materials, language issues, and the cost of shipping each accounted for about 25% of concerns; security and safety accounted for 17%, with cultural issues and political crises that might impede cross-border travel or shipment accounting for only about 2% overall.

And finally, we asked “If your company is not currently manufacturing in another country, which of the following factors would lead you to consider doing so?” The answers seem to sum up the major points — upon which this issue’s articles and staff-written features are based:

- economic incentives (taxes, enterprise zones, research parks) 42%

- decreased cost of labor/training and other personnel issues (41%)

- established distribution channels for expanding into new markets (39%)

- improvements in supply-chain management (29%)

- better security (against counterfeiting, IP infringement, terrorism, and natural disasters, 18%)

- ability to monitor cold-chain storage and shipping units remotely (18%)

- harmonization of regulatory requirements (12%).

The full set of figures and tables derived from this survey will be available in mid to late June at www.bioprocessintl.com/bpiextra. We also thank the contributors to this issue for addressing a number of important criteria for successful expansion of biomanufacturing operations worldwide.

Author Details

S. Anne Montgomery is editor in chief of BioProcess International, 1574 Coburg Road #242, Eugene, OR 97431; 1-646-957-8877, amontgomery@bioprocessintl.com.