Biopharmaceutical medicinal products (biologics) had an estimated global commercial market size of US$100 billion in 2013. Because they are more complex than small molecules — and defined by the uniqueness of their manufacturing processes — the generics approval process is not applicable for biologics. Article 10(4) of European Medicines Agency (EMA) directive 2001/83/EC was amended in 2004 in response to the industry’s desire for market access by launching a “similar” biologic abbreviated approval pathway.

Leading the subsequent process, the EMA issued a dedicated guidance for industry on the topic of biosimilars (1). The guidance can be described as a response or accompaniment to a biosimilar development program, which prompted guidance to be issued case by case. Three hierarchical layers of documentation were created. The first layer contains general guidance on the principle of the biosimilar approach. The middle layer contains general guidance on clinical topics such as safety and efficacy and on nonclinical topics such as quality. The lower layer (product-class specific) was until recently still being updated for increasingly complex biologic product classes. On the basis of experience gained with biosimilars so far, the EMA will be introducing a second- generation series of guidance documents that take into account the past, current, and possible future challenges for such products (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hierarchical overview of EU biosimilar past, current, and proposed overarching guide, general guides, and MAb-specific guidance; other product-specific guides were not analyzed and thus are not represented.

A biologic is defined through its quality profile, which in all such products (both reference biologics and biosimilars) can change over time. Changes can result from variations in raw materials and/or conditions during manufacturing, increase in production scale, or site transfers that usually include changes in raw materials and production equipment. Such changes can lead to different quality profiles (2, 3). One lot of a biologic produced is never 100% identical to other lots (2, 4, 5).

Failure to detect those inherent quality-profile changes reveals a failure to design sufficiently sensitive test methods. Uncertainty accompanying the consequences of those unforeseen (dynamic) shifts and/or changes in quality profile is greater for larger biologics such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) than for smaller, less glycosylated, and less complex biologics — and traditional (chemical) medicinal products — because more potential effects on quality attributes need to be taken into account.

For biosimilar products, the key problem is that a biosimilar developer has to match the quality profile of its product to that of a reference biologic, which can change at any point in time. This creates a requirement for controlling the dynamic quality profile of the biosimilar and matching that to the dynamic quality profile of the reference biologic. It is comparable to a situation in automobile traffic, in which one driver tries to match speed with that of another car, but the driver can control only his or her own speed while the other accelerates independently. Matching the speed of two cars can be complicated if the second driver changes speed unforeseeably.

Biosimilar developers usually monitor and analyze multiple reference biologic lots over extended periods. However, the number of lots analyzed allows for only limited conclusions. When a situation occurs in which the reference quality profile of an innovator biologic shifts/ changes, the biosimilar developer and regulatory authorities must judge how to proceed. The regulatory process involved in making such judgments is still in its infancy, and available guidance from the EMA is not clear enough (6).

Methods

Literature Research: We conducted a multilayer literature search. First we systematically consulted the websites of the EMA and analyzed selected biosimilar guidance documents. We also searched publications on the topic using MEDLINE (PubMed) and Gabi-online. Our key search terms were combinations of these words: biosimilar and heterogeneity or variation or life-cycle. These searches were limited to full-text English-language articles.

Questionnaires:

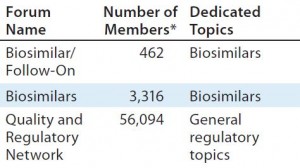

We also implemented two questionnaires. The first questionnaire (QI) was published online using the “Survey Monkey” online survey tool. We posted a link to that survey page to LinkedIn forums for members with interests related to the biologic and biosimilar fields (Table 1). Our second questionnaire (QII) went to experts in the field of biosimilars whom we identified either through their submissions and participation in drafting of the EMA’s guideline on MAb-containing biosimilars (7) or participation in a workshop run by the EMA related to that document.

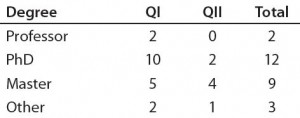

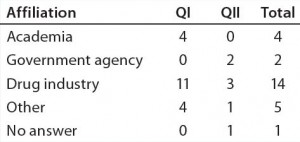

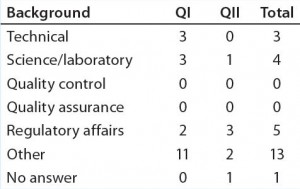

Table 2a: Educational and professional backgrounds of questionnaire participants — highest academic degree attained (n = 26)

QI = Questionnaire #1, QII = Questionnaire #2

Note: To increase the response rate and protect the participants, we assured confidentiality for all participants in Questionnaires I and II. However, their educational and professional backgrounds were indicated so that their proficiency related to the topic could be estimated (Table 2). We acknowledge that neither questionnaire withstands statistical examination because the number of

Table 2b: Educational and professional backgrounds of questionnaire participants — professional affiliation (n = 26)

participants and response rates were rather low. However, our results do provide a valuable snapshot of views in the wider biosimilar community on the topic of quality profile dynamics.

Results

Figure 1 outlines our EMA guidance document review. The EMA requires in its guidance documents

Table 2c: Educational and professional backgrounds of questionnaire participants — professional background (n = 26)

that developers account for differences in purity and impurity profiles between innovator biologics and biosimilars (1). However, the EMA acknowledges that their quality profiles are allowed to drift from one another after marketing authorization is granted. “It should also be noted that there is no regulatory requirement for redemonstration of biosimilarity once the Marketing Authorization is granted,” according to the newly proposed guide (6).

The only mention of changes during the development and approval process in EMA’s Biologic Working Party (BWP) documents is as follows:

“It is acknowledged that the manufacturing process of the reference medicinal product evolves through its lifecycle, which may lead to detectable differences in some quality attributes. Such events could occur during the development of a biosimilar medicinal product and may result in a development according to a QTPP [quality target product profile] which is no longer fully representative of the reference medicinal product available on the market. The ranges identified before and after the observed shift in quality profile could normally be used to support the biosimilar comparability exercise at the quality level, as either range is representative of the reference medicinal product.” (6)

The quality-issues concept paper on the guideline revision emphasizes the life cycle of a biosimilar product (8), leading us to the following questions: Does a biosimilar need to achieve a quality profile that falls within that of the reference biologic? Under what circumstances could a biosimilar developer deviate from such an approach? This is directly related to the development strategy that a biosimilar developer should take.

The BWP recommends in its adopted guide to characterize the reference biologic because the “biosimilar relies in part on the scientific knowledge gained from the reference” (6). That comes from analyzing multiple lots of a reference biologic (at different stages in its shelf life) in line with 76% of our expert questionnaire responses that “multiple lots of the reference biologic need to be part of any comparability exercise.” So the implications remain unclear for the dynamics of quality profiles, particularly regarding their effects on the continuation of comparability exercises, including clinical trials.

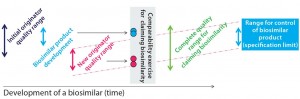

Review of Publications: Our review of the development strategy for biosimilars did reveal a lack of working concepts. In fact, the only comprehensive strategy we found was published in 2011 (9). The authors are associated with Sandoz, a major biosimilar company. They describe the quality profile of a reference biologic and that of a biosimilar in development (Figure 2a).

Figure 2a: A proposed biosimilar development approach to tackle quality shifts outlined by McCamish and Woollett (10) shows the “initial originator quality range” (that of the reference biologic) in dark blue. The range of the biosimilar’s quality profile is in light blue. Clearly, the latter profile fits within the limits of the former. Then in pink, the quality profile of the reference biologic has changed, whereas the quality profile of the biosimilar did not. With dissimilar quality profiles, a comparability exercise must be carried out.

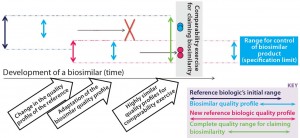

Figure 2b: In our proposed biosimilar development approach for tackling quality shifts, the “initial originator quality range” (that of the reference biologic) is in dark blue. The range of the biosimilar’s quality profile is in light blue. Clearly, the latter profile fits within the limits of the former. Then in pink, the quality profile of the reference biologic has changed. That new quality profile is adopted by the biosimilar, and a comparability exercise is carried out based on these highly similar quality profiles. The new allowable quality range (quality profile) for the biosimilar is limited by the reference biologic’s new quality profile

Figure 2a clearly shows that the quality profiles of reference biologics change and evolve over time. In particular, a comparability exercise is conducted based on different quality profiles of the two respective biologics (innovator and biosimilar), which do not overlap. When comparability studies conducted by a biosimilar developer indicate differences between those products, and the likely root cause is a shift in the quality profile of the reference biologic, no indication of “how to proceed” yet exists.

Kowid Ho (a former BWP member) has been quoted in saying that the quality profile of a reference biologic may well be dynamic over its entire life cycle (10). His view is that “changes in quality attributes could occur and be accepted if it is demonstrated that there is no negative impact on safety and efficacy. This could lead to a drift of some quality attributes over time, which may become a challenge to development of a biosimilar product, particularly when defining the target variability of reference product attributes.” Ho also raised the question of whether biosimilars can truly remain similar throughout their entire life cycle. “They will also have their own and independent life cycle once they receive marketing authorization” (10).

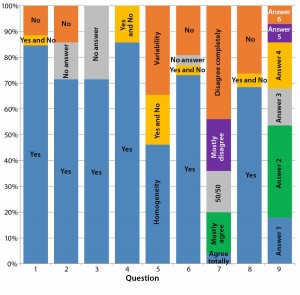

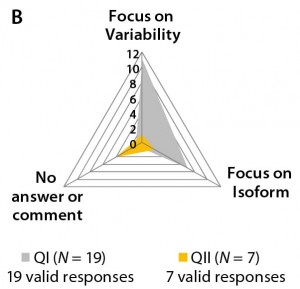

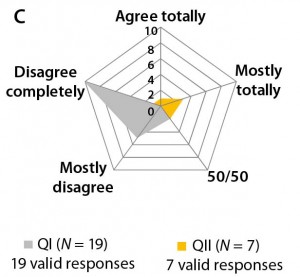

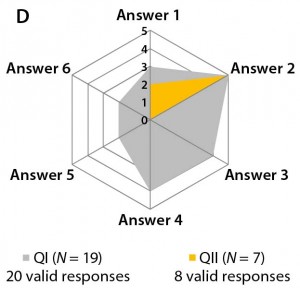

Questionnaires I and II: The “Questions and Answers” box outlines the questions and multiple-choice answers in Questionnaires I and II. Figure 3 summarizes the results we obtained. The questions were divided into three sets: 1–4, 5–8, and 9.

Figure 3a: Our summary analysis of answers to questions 1–9 groups answers as percentages to Questionnaire I (QI), Questionnaire II (QII), or both (QI + QII). For questions 1–4, 6, and 8, “Yes” or “No” answers were required. The percentage of positive answers (“Yes”) is shown in blue; the percentage of negative answers (“No”) in red. Gray indicates where participants declined to give an answer (“No answer or comment”). Orange indicates where participants answered both “Yes” and “No.” For questions 5 and 9, multiple choices were given. One participant each in QI and QII chose both answers for question 9, which gave us 28 valid answers.

The first set (questions 1–4) sought a consensus among participants related to the dynamics of the biologics quality profiles. Most participants in both questionnaires agree that such dynamics exist. That is directly revealed by the answers to question 1: A direct consequence of the dynamic is to assess its extent using multiple lots, reflecting the dynamic over a given period of time. Using one lot each of a reference biologic and biosimilar is insufficient; doing so is clearly not practiced in the industry. Responses to questions 2–4 reconfirm that train of thought.

The second set of questions (5–8) was concerned with consequences of the quality-profile dynamic for biosimilar development. Questionnaire respondents have differing opinions on these consequences during development of a biosimilar.

Different answers to question 5 regarding “the biosimilar development aim” — whether to focus on the major isoform (homogeneity) and reduce heterogeneity and purity variation of the active substance or to focus on all isoforms (identity, ratio, and quantity) — can be interpreted as a sign of uncertainty and lack of working concepts for biosimilar development. Note that most participants in Questionnaire II declined to answer this question (Figure 3b).

Differences in the answers to question 7 can be interpreted as a sign of differing perceptions on clinical trial outcomes based on different quality profiles (Figure 3c). Most participants in both agree that boundaries for development of biosimilars are set by the quality profile of the reference biologic. However, most participants in Questionnaire I say that deviations from that profile are permissible.

Figure 3b–d: Detailed analysis of questions 5, 7, and 9 shows differences in answers between participants in QI and QII. The gray spider-web format highlights answer patterns, and a pie chart shows percent distribution of answers for each question.

The third set consists only of question 9, evaluating the potential consequences of these dynamic quality profiles. Most participants in both questionnaires expect that the regulatory authority (EMA) will ensure comparability of a reference biologic to itself. However, their view may conflict with findings from questions 5 and 7. It is remarkable that among participants in Questionnaire I, all possible answers were selected, with higher weightings on answers 2 (25%), 3 (20%), and 4 (20%). But Figure 3d shows that participants in Questionnaire II mainly choose answer 2 (62%). Thus, a lack of clarity exists regarding how to proceed with clinical trials when the quality profiles of innovator biologics and biosimilars differ.

Discussion

Our data highlight an area of tension and uncertainty regarding the dynamics of quality profiles for reference biologics and biosimilars during development of the latter, not only between the regulator (EMA) and the biopharmaceutical industry, but also within the biosimilar community itself. When comparing answers to questions 5 and 7 with answers to question 9 (all related to the practical and regulatory consequences of these dynamics), we found differences among “similar” questions and related follow-up questions. Biosimilar developers require guidance on the EMA’s expectations in regard to these quality profiles. Companies need to know the extent to which a biosimilar must be similar to the reference biologic when the dynamic nature of the latter is taken into account. Thus we forwarded the following comments to the EMA as part of its guidance review process for the revision 1 draft guideline on biosimilars:

“The initial or cardinal biosimilar development aim is to mimic the quality profile of the reference biologic drug substance including its variation/heterogeneity (on a lot basis) where possible.” (6)

“The better the correlation of the molecular characteristic (including process understanding) of the biosimilar drug substance with quality attributes is understood, the more the biosimilar developer can shift the focus (of the development strategy) from mimicking the Q-profile of the reference biologic, including its variability/heterogeneity, towards manufacturing a more consistent/pure biosimilar drug substance; and therefore, eliminating some of the heterogeneity of the reference biologic, as long as the safety and efficacy remain comparable within the margins of equivalence.” (6)

A reference biologic should set the boundaries (including its own heterogeneity and variation) for its biosimilar counterpart. Those boundaries are essential for a coherent development strategy.

The guideline revision has now been adopted (6). We believe that the EMA’s response to comments on the draft, with only minor changes made to the “adopted” guideline, indicate reluctance for a clear position on these issues.

From a biosimilar developer’s perspective, it is sensible to mimic the purities and impurities of a reference biologic and justify why the biosimilar is less impure (e.g., has a more pure quality profile with less heterogeneity and variation).

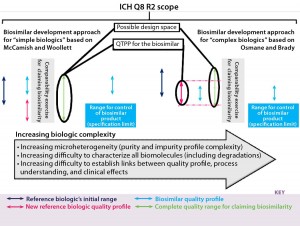

McCamish and Woollett’s proposed comparability exercise based on different quality profiles of a reference biologic and biosimilar is not recommended for complex biologics (Figure 2a). For non-MAb products, the relation of molecular characteristics and quality attributes cannot be fully understood with a level of confidence that is commensurate with the complexity of such biomolecules. That would pose a risk for complex biologics, so we recommend a development approach as outlined in Figure 2b. The major pitfall for biosimilar developers in following that approach is designing a product with less heterogeneity and variation than the original product has. As a consequence, a different (strictly considered new) product is being developed, so the biosimilar guidance and approval process no longer applies. The Figure 2b development approach tackles this potential pitfall well.

Quality by design (QbD) should be integrated with the approaches outlined in Figures 2a and 2b and therefore be mandatory for developing a biosimilar. If the biosimilar developer established a design space for that product, then it would be possible to adapt its quality profile to a possible new one for the reference biologic. The biosimilar quality profile would be matched and adapted to the most recent quality profile of the reference biologic (assuming that a change happened for the reference biologic, and the quality profiles were determined to be dissimilar at that stage). This is complementary to the Figure 2a and Figure 2b approaches and ensures that during the clinical phases the best possible foundation for a successful (and therefore, short) clinical comparability exercise are set (Figure 4). The “A-MAb case study” is a comprehensive example introducing the concepts of ICH Q8 R2, including a design space for complex biomolecules (11).

Figure 4: We found differences and similarities in biosimilar development approaches. The “initial originator quality range” is that range of the reference biologic in dark blue. The quality profile range for the biosimilar is in light blue. Then in pink, the quality profile of the reference biologic has changed. That new quality profile is adopted for the biosimilar, and a comparability exercise is carried out based on highly similar quality profiles. On the left side, the biosimilar’s quality profile does not fit within limits of that for the reference biologic’s recent quality profile shift; on the right side, the biosimilar’s quality profile does fit within limits of that for the reference biologic’s recent quality profile shift. Right and left biosimilar quality profiles fit within the complete quality range for claiming biosimilarity, whereas the quality target product profile (QTPP) for the biosimilar differs.

More Guidance Is Needed

The EMA has made it clear that once a market authorization is granted for a biosimilar product, the agency expects biosimilars to vary independently of their corresponding innovator products (10). However, this bears unsolved implications for the interchangeability of such products. Dynamics of the quality profiles for the reference biologic and its biosimilar counterpart might well lead over time to differences in their safety and efficacy profiles (12).

Questions and Answers for Questionnaires I and II

Questions

1: Do multiple lots of the biosimilar against multiple lots of a reference biologic need to be part of comparability exercises? (n = 26)

2: Will one lot of a complex biologic (e.g., a MAb) always contain molecular variations (due to product- or process-related heterogeneity) that are slightly different from each other? (n = 7)

3: Is the ratio of those slightly different (MAb)-molecules unique for an individual lot? (n = 7)

4: Among multiple lots of a complex biologic (e.g., a MAb), will there always be variation of the quality profile (due to product- or process-related variation and/or process changes)? (n = 7)

5: Should a biosimilar developer focus on mimicking the quality profile of the reference biologic including all its variability or focus on homogeneity (e.g., of the major isoform)? (n = 26)

6: Do multiple lots of a reference biologic need to be analyzed for a biosimilar developer to understand the allowable limits for its biosimilar manufacturing specification? (n = 26)

7: How much would you agree with the following sentence? “The quality profile of a biosimilar should fall within the limits of the quality profile of the innovator biologic because one would expect safety and efficacy to be similar too.” (n = 26)

8: Would you agree with the following statements? “The initial or cardinal biosimilar development aim is to mimic the quality profile of a reference biologic drug substance including its variation or heterogeneity (by lot) where possible. . . . The better the correlation of molecular characteristics (including process understanding) of a biosimilar drug substance with quality attributes is understood, the more that product’s developer can shift its development-strategy focus from mimicking the quality profile of the reference biologic (including its variability and heterogeneity) toward manufacturing a more consistent and pure biosimilar drug substance — therefore eliminating some of the reference product’s heterogeneity — as long as safety and efficacy remain comparable within the margins of equivalence.” (n = 19)

9: Would you recommend that a biosimilar developer initiate clinical trials (a clinical comparability exercise) if the reference biologic’s quality profile shifted and the quality target product profile (QTPP) of the biosimilar is based on the “old” profile? (n = 26, 28 answers)

Multiple-Choice Answers to Question 9

1: Yes, because the risk of detecting a clinically significant difference due to changes of the quality profile is relatively low risk for the biosimilar developer.

2: Yes, because the reference biologic’s “new” quality profile was approved by the EMA and therefore should fall within similar safety and efficacy margins as the “old” profile (so it should not affect the clinical comparability exercise).

3: Yes, because when clinical comparability exercise differences in are detected, the biosimilar’s quality profile can be adjusted rapidly to follow the most recent profile of the reference biologic.

4: No, because the biosimilar should have (before the clinical comparability exercise) a very similar quality profile to that of the reference biologic. This should lead to a similar clinical outcome.

5: No, because differences in comparability beyond the margin or tolerance would require additional investigation, and the burden of such investigations is deemed undesirable.

6: No, because the risk of detecting a clinically significant difference due to quality profile changes is relatively high for the biosimilar developer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Dogsten, PhD, for editing and improving the text of this publication.

References

1 CHMP/437/04. Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products. EMEA: London, UK, 30 October 2005; www.ema.europa.eu/ docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_ guideline/2009/09/WC500003517.pdf.

2 Apffel A, et al. Application of New Analytical Technology to the Production of a “Well-Characterized Biological.” Dev. Biolog. Standardization 96, 1998: 11–25.

3 Berger M, Kaup M, Blanchard V. Protein Glycosylation and Its Impact on Biotechnology. Adv. Biochem. Eng./Biotechnol. 127, 2012: 165–185.

4 Kresse GB. Biosimilars: Science, Status, and Strategic Perspective. Euro. J. Pharmaceut. Biopharmaceut. 72(3) 2009: 479–86.

5 Pizarro SA, et al. Biomanufacturing Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Application for Downstream Processing: Using Dissolved Oxygen As an Indicator of Product Quality for a Protein Refolding Reaction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 104(2) 2009: 340–351.

6 EMA/CHMP/BWP/247713/2012. Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology-Derived Proteins As Active Substance: Quality Issues (Revision 1). European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2012.

7 EMA/CHMP/BMWP/403543/2010. Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Monoclonal Antibodies: Non- Clinical and Clinical Issues. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, November, 2010.

8 EMA/CHMP/BWP/617111/2010. Concept Paper on the Revision of the Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology-Derived Proteins As Active Substance: Non-Clinical and Clinical Issues. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, September, 2011.

9 McCamish M, Woollett G. Worldwide Experience with Biosimilar Development. mAbs 3(2) 2011: 209–217.

10 Reichert JM. Next Generation and Biosimilar Monoclonal Antibodies: Essential Considerations Towards Regulatory Acceptance in Europe. mAbs 3(3) 2011: 223–240.

11 CMC Biotech Working Group. A-MAb Case Study in Bioprocess Development. California Separation Science Society: Emeryville, CA, 2009; http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.casss.org/ resource/resmgr/imported/A-Mab_Case_ Study_Version_2-1.pdf.

12 Declerck PJ, et al. Biosimilars: Controversies As Illustrated By rhGH. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 26(5) 2010: 1219–1229.

Corresponding author Malik Osmane (Diplom Biologe; MSc. pharm. QA/RA) is a process development engineer for Crucell Bern, a vaccine company in Switzerland; malikosmane@gmail.com. Joseph Brady, PhD, is director of global compliance and validation at Zenith Technologies as well as a lecturer at the Dublin Institute of Technology.

Disclaimer: Both authors work in the life- science industry; however, neither is professionally involved with biosimilars. No conflict of interest exists, and the industry was not involved with the work nor did it supply any funding. The interest to carry out this research arose from purely academic reasons.