A virus validation study is required for virus-removal filters prior to employing them in a biopharmaceutical purification process. Validation conditions are determined on a case-by-case basis by each filter user. Optimizing conditions for removal of parvovirus is important to achieve LRV = 4. However, the optimal conditions are often unclear for validation studies, because each product may behave differently. We attempt to establish optimal conditions for human IgG and show the effects of varying IgG concentration, purity of the virus spike, and the spike percentage on the performance of Planova® virus-removal filter in a model validation study.

Materials and MethodsFor the porcine parvovirus (PPV) preparations used in the spiking experiments, serum or serum-free PPV supernatants were collected, centrifuged at low speed, and 0.45-µm filtered to obtain stock solutions. In the case of purified PPV, following 0.45-µm filtration, ultracentrifugation, and density gradient centrifugation was applied. Serum, serum-free, and purified PPV solutions were then used for spiking. Spike amounts were 0.5 or 3.0 vol% for serum-free PPV, 1.0 vol% for serum PPV, and 0.01 vol% for purified PPV. Concentrations of human IgG were 1–30 mg/mL. All IgG solutions, spiked and non-spiked, were prefiltered by Planova®35N to remove aggregates. All virus filtrations were conducted using Planova®20N virus filters. Filtrations were performed in dead-end mode at a constant pressure of 0.8 kgf/cm2 (11.4 psi)

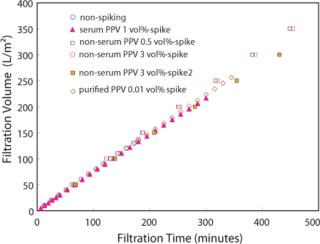

Results and DiscussionsV/m2 profiles of different purity PPV spikes were nearly identical (Figure 1) and were unaffected by the existence of PPV or the preparation methods with 5 mg/mL human IgG. Notably, the less pure PPV preparations spiked at 1% filtered identically to conditions with purified PPV and without PPV. The presence or absence of serum in the virus preparation also did not affect the profile.

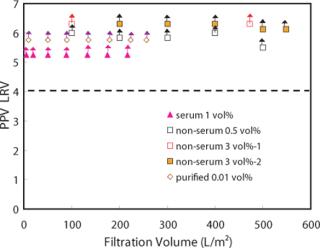

A PPV LRV greater than 4 was maintained over the filtration volume of 200 L/m2 under any spiking conditions used herein (Figure 2). In particular, for a non-serum PPV spike of 3%, a PPV LRV greater than 4 was maintained over 500 L/m2. If a 3% spike condition is expected to change the product condition significantly so as to affect the virus filtration result or flux profile, we didn’t see that effect here.

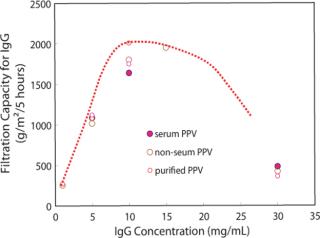

Furthermore, we investigated the relationship of IgG filtration capacity to IgG concentration for Planova 20N. In this case we define filtration capacity as the amount of IgG filtered for five hours, to IgG concentration (Figure 3). We were looking to establish optimal throughput while maintaining LRV greater than 4. At each IgG concentration, the five-hour capacity level was unaffected by the various purities of virus spiking material. We can see in Figure 3, from the viewpoint of maintaining viral safety while maximizing productivity, that the most economical IgG concentration appears to be from 10 to 20 mg/ml, with a slight peak at 10 mg/ml.

Under the conditions tested herein, the capacity of Planova®20N for virus filtration is shown to be quite large and well suited for current industry practice. How do we explain this capacity? From the SEM membrane structure analysis (not shown), Planova®20N membrane is shown to have a microporous thick dense layer (not skin) for virus removal of 30 µm (1). The large virus trapping capacity, even under extreme filtrate conditions (in this case IgG and less pure virus preparations) is most likely because of this thick virus removal layer.

ConclusionsPlanova®20N virus-removal filters show predictable and well-balanced performances that are unaffected by varying IgG concentration, virus purity, and spike amount, (e.g., constant protein filterability and consistent high LRV). In addition, the virus trapping capacity of Planova®20N is large in a wide range of IgG concentration. We propose that the Planova®20N virus removal filter is a robust and economical means for a bioprocess virus removal step.